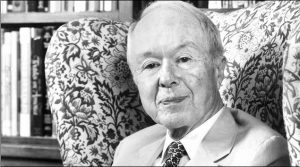

June 20, 2017 Abbott Lowell Cummings- A Remembrance

Matthew Kiefer, Co-chair of HBI’s Council of Advisors, marks the passing of architectural historian Abbott Lowell Cummings with memories of Cumming’s many contributions to the field of historic preservation, and his devotion to teaching and learning.

Abbott Lowell Cummings, the pre-eminent New England architectural historian and preservationist, died at the age of 94, just before Memorial Day, in Hadley Massachusetts, near his longtime home in South Deerfield.

How fitting that Abbott, who devoted his long life and career to illuminating the cultural landscape of early New England, would pass away at a national holiday devoted to memory. Abbott traced his professional lineage to New England’s preservation progenitor, William Sumner Appleton, the founder of Historic New England (then called the Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities.) Abbott influenced and mentored generations of Boston preservationists during his decades as head of SPNEA and as a professor in in Boston University’s Preservation Studies Program, which he helped found.

Abbott was lucky to find his calling early. As a teenager, he developed what became a lifelong devotion to early New England architecture, which he pursued with an unusual combination of meticulousness and enthusiasm. He especially focused on everyday buildings from the first period of English settlement of New England, before the more formal Georgian style took over. These “First Period” houses were handmade of heavy timber by unschooled artisans, using post-Medieval building practices transported from the Old World.

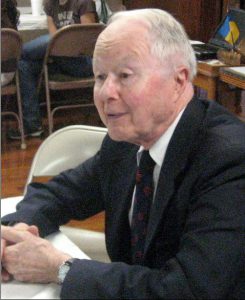

He explored their stylistic influences, their furnishings and especially their innards, taking pains to include careful sketches of joinery in his seminal 1979 book, The Framed Houses of Massachusetts Bay, 1625-1725. He never lost the joy of untangling the origins of these early buildings and the people who made them?thus his parallel interest in New England genealogy.

Abbott was as concerned with preserving these rare cultural artifacts as with studying them. He loved to tell the story of William Sumner Appleton discovering the early 18th century Pierce-Hichborn house, obscured behind later facade “improvements”, from a newspaper story about a raid on a North End bookie joint. Behind the bookie, surprised by a police photographer, was a fireplace with a bolection molding a dead giveaway! Appleton rushed to the rescue, and the building is preserved to this day.

Abbott’s zeal kindled the enthusiasm of many, many others, including my own. As a BU undergraduate, I took his course in early New England architecture, taught in the evening at SPNEA’s Harrison Gray Otis House. It ignited something, and before long, I had the good fortune be accepted into his graduate seminar in first period buildings.

We 6 devotees met at a different handmade house every week, dressed in old clothes with flashlights handy, where Abbott would give us an assignment. At the heavily restored Hichborn House, our charge was to determine what was original and what was restored. At the as-yet unrestored Pierce House in Dorchester, it was to determine the construction sequence.

After an hour of exploration, we would assemble to report our findings. Abbott was as excited as we were when we deduced correctly; when we were stumped, he would patiently lead us to the answer, sometimes literally. (At the Pierce House, the attic framing was the key.)

Early in his career, Abbott’s research was used, uncredited, by an eminent architectural historian. I was the happy beneficiary of Abbott’s resolve never to repeat this transgression. He had commissioned a piece for Old Time New England on the James Blake House in Dorchester, the oldest house in Boston, whose 17th century date had never been corroborated.

While the research was thorough, Abbott did not feel the writing was up to snuff, so he asked me to re-write it for publication. Without my asking, Abbott insured that the published version credited me with editorial assistance, just below the name of the author.

Abbott’s devotion to advancing knowledge made him generous with his time and insights. Several years ago, urban geographer Arthur Krim became interested in the handful of surviving buildings in central Boston built after the Great Fire of 1711. HBI’s flagship, the Old Corner Bookstore, is one; another is the Union Oyster House, whose unusual canted facade had never been explained.

Arthur’s research suggested an explanation to me, related to an early 19th century widening of Marshall Street. When I outlined my hypothesis to Abbott, he exclaimed: “Dear boy,” (I was approaching 50 at the time) “I think you’re on to something!” He put us in touch with others who helped decode the construction sequence in-you may have guessed this the attic framing.

For an antiquarian, Abbott was deeply engaged with the modern world. After his retirement, we had more than one lively discussion over dinner at the Deerfield Inn, where Abbott was known to the staff by name, and where his informed and progressive political views were evident. One dinner included my pre-teenage daughters, whom Abbott engaged as effortlessly as he had me decades earlier.

Abbott was appropriately named; there was something almost ecclesiastical about his devotion to his field, to which he made enormous contributions. He left indelible memories to all who knew him. We at Historic Boston acknowledge our debt to him, and honor his memory.