August 1, 2017 What Did Faneuil Hall Really Look Like? It’s Time We Found Out

The second in a series of blog posts that focus on the exterior treatment of early American masonry structures, architectural historian, and co-founder of Archipedia New England, Brian Pfeiffer, suggests that the restoration choices of early preservationists on some of our greatest historic buildings today may not be as true to their origins as we think.

One of the great dangers of “restoration” is that it has been used in a poorly defined way for the past century, often altering an historic building to fit a romanticized notion of its original appearance.

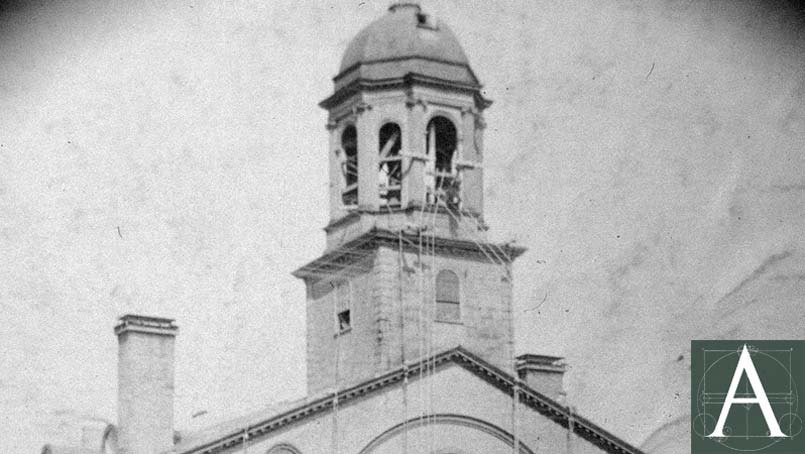

Figure 1 – ca. 1856 view of Faneuil Hall (photo left) showing its masonry and woodwork painted [image courtesy of the Bostonian Society]

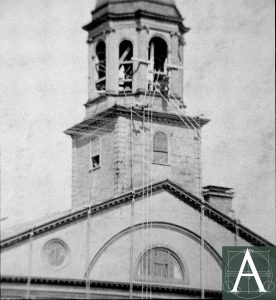

Figure 2 – Faneuil Hall with swing staging and scaffolds during repainting ca. 1890 [image courtesy of Historic New England]

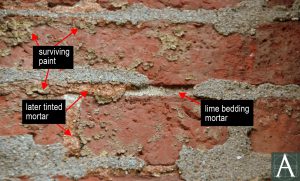

During this same period other landmarks such as the Old South Meeting House and Old State House were stripped of their paint. These actions were not guided by historical research or examination of existing paint layers, but rather by notions of the picturesqueness of handmade materials materials that would generally have been painted or plastered by their makers. These decisions set a path followed by thousands of others to the detriment of pre-industrial masonry buildings throughout New England.

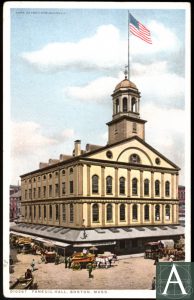

Figure 3 – Faneuil Hall (ca. 1916-1924) as it may have appeared before its paint was removed – postcard view of a colorized black & white photograph [Image courtesy of the Bostonian Society]

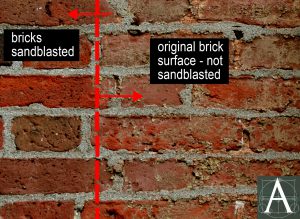

The loss of coatings is not only an aesthetic concern. Coatings of lime wash, paint and plaster have long histories in pre-industrial Britain and the United States to reduce the amount of moisture absorbed into walls of soft-fired brick and to absorb moisture across wide surfaces to promote speedy evaporation. Surviving examples can be seen in New England on walls that have been protected from weather, such as the former west gable end of the Spencer-Peirce-Little House (ca. 1690) in Newbury, Massachusetts. Builders guides of the nineteenth century advised that the thickness of a wall could be reduced if the wall were coated. With the protective skin of the bricks damaged by sandblasting and their softer, more absorptive cores exposed, the building is more vulnerable to damage from an increasingly violent climate.

Figure 4 – view of brick surfaces damaged by 1923 sandblasting (photo left) and original brick surfaces protected from sandblasting (photo right)

Figure 5 – brick with fragmentary paint evidence and original fired surfaces protected from 1923 sandblasting