29 Mar 2019 11 Things You Should Know about Phillis Wheatley

In recognition of Women’s History Month, we spent some time reviewing primary source documents and secondary readings to learn more about literary icon, Phillis Wheatley, an enslaved West African child turned educated woman and author. Whether you have read her published poems or walked by her Boston Women’s Memorial statue between Fairfield Street and Gloucester Street on Commonwealth Avenue, explore our selection of facts from the life and career of Phillis Wheatley. We hope from our brief selection readers will delve deeper into Wheatley’s life with the list of links at the end of the post.

1. Phillis Wheatley (1753-1784) was an enslaved woman from West Africa, who gained international fame for her book, Poems on Various Subjects.

2. The most comprehensive account of Phillis Wheatley’s life was published by Margaretta Matilda Odell in a book entitled, Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, A Native African and a Slave. The book was published by George W. Light in Boston in 1834. Light also produced the first American publication of Wheatley’s book of poetry in 1834.**

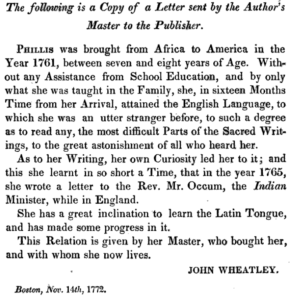

3. Phillis Wheatley assumed her surname from John Wheatley, the man who purchased her as a “faithful domestic” for his wife, Susannah. Her first name Phillis was the name of the ship that brought her to America.

4. It is estimated that Phillis was seven or eight years old at the time of her purchase, based on the rate that she was losing her baby teeth.

5. A short time after Phillis arrived at the Wheatley house on King Street in Boston (now State Street), the Wheatley’s young children, Mary and Nathaniel, introduced her to writing letters with chalk. After displaying great scholastic aptitude, Phillis was allowed to learn to read and write. Odell’s book reports that, “she [Phillis] was not devoted to menial occupations, as was at first intended; nor was she allowed to associate with the other domestics of the family, who were of her own color and condition, but was kept constantly about the person of her mistress”. Phillis was the only enslaved person in the household that received the luxury of an education.

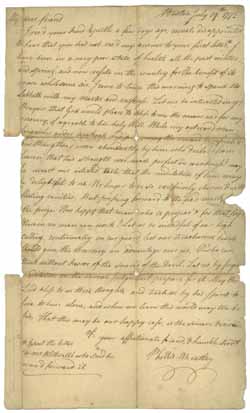

6. As a child, Phillis was isolated from the enslaved and free black communities, but as a freed adult, she was associated the African Union Society through her closest friend, an enslaved woman named Obour Tanner. At least seven letters between the two women survive in the historical record, indicating that Wheatley’s ties to African-American New England influenced her life and writing just as strongly as Boston’s white elite.

7. In December 1767, as a young teenager, Phillis’ first published poem appeared in the Newport Mercury, “On Messrs. Hussey and Coffin”.

8. Due to her race and assumed illiteracy, Phillis was required to prove that she was indeed the author of her book of poems by a group of men, which included John Erving, Reverend Charles Chauncey, John Hancock, Thomas Hutchinson, the governor of Massachusetts, and his Lieutenant Governor, Andrew Oliver. The group concluded that Phillis had written the poems and printed their signatures in the book as confirmation of that fact.

9. In December of 1775, Wheatley wrote a letter to George Washington, who had just been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army, containing an ode written in his honor: “Proceed, great chief, with virtue on thy side, / Thy ev’ry action let the goddess guide. / A crown, a mansion, and a throne that shine, / With gold unfading, WASHINGTON! Be thine.” Washington responded to Wheatley expressing his appreciation for the poem, and later invited her to call at his headquarters in Cambridge.

10. The only surviving portrait of Phillis Wheatley is the engraving commissioned by Selina Hastings Countess of Huntingdon of England. The image was engraved by African painter, Scipio Moorhead.

11. To this day, no one knows where Phillis was buried. Like Wheatley’s enslaved contemporaries, she was buried in an unmarked grave. Odell laments that Phillis’ intellect and artistic genius represents the lost potential of the millions who never enjoyed her opportunity to learn, and calls Wheatley “an encouragement and a gratification to those gifted spirits, unto whom the lines have fallen in the shade-places of life, but who aspire to pitch their tent in the sunshine”. Odell suggests that Wheatley is more than “a solitary instance of African genius” and other slaves of her intelligence and talent could have published produced art and published work if only they had fallen into more “generous and affectionate hands” and avoided the “privations and exertions of common servitude”.

** Light was one publisher in a very long list of publishers that conducted business on Cornhill Street. In the 19th and 20th century, the street was a bustling area near what is presently Court Street and Scollay Square. In the 19th century, it was the home of many bookstores and publishing companies. Light’s publishing house was about half a mile from Ticknor and Fields. Isaac Knapp, a contemporary of Light, also published Wheatley’s book of poetry in 1838. Knapp’s publishing house was well-known for its printing of The Liberator, an anti-slavery newspaper with his partner William Lloyd Garrison.

Sources to explore:

- Cover image: http://www.aviewoncities.com/gallery/showpicture.htm?key=kveus3042

- https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/phillis-wheatley

- https://www.masshist.org/database/773

- http://bostonlitdistrict.org/venue/old-south-meeting-house-and-phillis-wheatley-1753-1784/

- https://collections.dartmouth.edu/occom/html/ctx/personography/pers0574.ocp.html

- https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/phillis-wheatley

- http://www.pwacleveland.org/bio

- https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/phillis-wheatley/