07 Mar 5 Epic Boston Love Stories and their historic places

In honor of Valentine’s Day 2023, we highlight historic spots associated with five great Boston love stories of the past. Come explore the city through rosy heart-shaped glasses!

-

- The Courting of Coretta Scott King (558 Massachusetts Avenue, South End)

In 1952 the young Boston University divinity school student Martin Luther King Jr. was introduced to Coretta Scott, a talented soprano studying voice at the New England Conservatory. Coretta resided in the building owned by the League of Women in Community

In 1952 the young Boston University divinity school student Martin Luther King Jr. was introduced to Coretta Scott, a talented soprano studying voice at the New England Conservatory. Coretta resided in the building owned by the League of Women in Community  Service, a civic organization for Black women at 558 Massachusetts Avenue in the South End. The League provided room and board for young black women attending college in Boston at a time when racial prejudice prevented their accommodation in college dormitories. Coretta lived here during the 18 months that she and Martin courted. They were married on June 18th, 1953 in Alabama but returned to Boston to complete their studies before Martin was called to the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, where the couple’s legendary life and work together began.

Service, a civic organization for Black women at 558 Massachusetts Avenue in the South End. The League provided room and board for young black women attending college in Boston at a time when racial prejudice prevented their accommodation in college dormitories. Coretta lived here during the 18 months that she and Martin courted. They were married on June 18th, 1953 in Alabama but returned to Boston to complete their studies before Martin was called to the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, where the couple’s legendary life and work together began.

The League of Women in Community Service, founded in 1918, still owns the historic 1858 townhouse facing on to Chester Square in the South End, and is currently undertaking a major capital campaign for restoration of the townhouse for the League’s second century there.

-

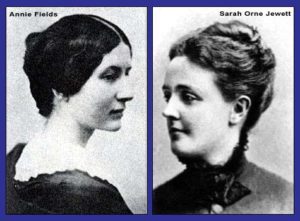

- Annie Fields and Sarah Orne Jewett’s Boston marriage (Charles Street, Beacon Hill)

The scene of two love stories – 148 Charles Street on Beacon Hill – was demolished in 1915, but the stories of its occupants survive in the writings of the many literary greats who visited during the life of Annie Fields (1834-1915). Annie and her husband James T. Fields were Boston’s arts and culture power couple. James, one half of the publishing house Ticknor and Fields, cultivated the 19th century’s greatest American and British authors, from Nathaniel Hawthorne to Louisa May Alcott. Annie, his second wife, was also a writer, and together they hosted readings and concerts their home, which at the time offered views of the Charles River. Their most well-known visitor was Charles Dickens, who stayed with the Fields’ in 1868.

James Fields died suddenly in 1881 and an inconsolable Annie retreated to Charles Street. Sarah Orne Jewett (1849-1909), one of the authors discovered and published by James Fields, visited Annie in late 1881 and never left. Their friendship evolved into a lifelong partnership that is frequently noted as a “Boston marriage,” the cohabitation of two financially independent unmarried women, which may or may not have been romantic.

Sarah died in 1909 at age 59. Annie Fields survived her second love and lived long enough to edit Sarah’s writings for publication.

-

- When (and where) Jack popped the question to Jackie (The Parker House Hotel, 60 School St, Boston)

It is said that then-Senator John F. Kennedy proposed to Jacqueline Bouvier in May of 1953 at table #40 in Parker’s Restaurant at the historic Parker House Hotel (today’s Omni Parker House).

One of the most important gathering places and hotels in Boston for nearly 200 years, the first Parker House was built in 1855 at the corner of Tremont and School Streets where it continues today. The present building– and the one that Jack and Jackie would have known – dates to 1927.

Jackie, a photographer for the Washington Times-Herald, and Congressman Jack Kennedy met in in Washington in 1951 and dated for two years  before their engagement and wedding in 1953. By 1960, Jack Kennedy had defeated Richard Nixon and become the youngest man elected President of the United States at 43, and Jackie, the youngest first lady at age 31.

before their engagement and wedding in 1953. By 1960, Jack Kennedy had defeated Richard Nixon and become the youngest man elected President of the United States at 43, and Jackie, the youngest first lady at age 31.

Some debate lingers about the precise place where Jack popped the question (was it in Washington, or was it in Boston?), but one thing that’s certain: the lavish engagement ring JFK presented to Jackie Bouvier featured a 2.84 carat emerald and a 2.88 carat diamond.

-

- Mayor and Mrs. James Michael Curley (The James Michael Curley House, 350 Jamaicaway, Jamaica Plain, and the Mary E. Hurley School, 493 Centre Street, Jamaica Plain)

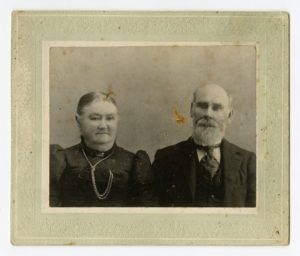

The legendary Mayor, Governor and Congressman James Michael Curley is known at once as “Mayor of the Poor” and the “Rascal King” for his many controversial years in politics and public service. His was a rags to riches story, extending from a humble start as the child of poor Irish immigrants in Roxbury to “the house with the shamrock shutters” in Jamaica Plain that he built in 1915.  His partner in that rise was Mary Emelda Herlihy, whom Curley married in 1906. Jim and Mary had nine children together and lived happily in the new house.

His partner in that rise was Mary Emelda Herlihy, whom Curley married in 1906. Jim and Mary had nine children together and lived happily in the new house.

However, tragedy befell the Curleys in 1930. After suffering with cancer for two years, Mary died, leaving James Michael Curley a bereft father of seven surviving children. With the loss of his beloved Mary, according to son Francis Curley, Jim Curley “lost his anchor.”

The private man was heartbroken; the public figure persisted and went on to become Governor in 1934.  In 1937 he married again, to Gertrude Casey, which was said to be a happy union. However, many close to him believe the loss of Mary marked the beginning of his political decline. It most certainly marked the beginning of a train of tragedies that befell his family. By the time of his death, only one of his nine children with Mary survived.

In 1937 he married again, to Gertrude Casey, which was said to be a happy union. However, many close to him believe the loss of Mary marked the beginning of his political decline. It most certainly marked the beginning of a train of tragedies that befell his family. By the time of his death, only one of his nine children with Mary survived.

Mary Emelda Herlihy’s name lives on in “The Curley,” the art-deco Mary E. Curley School in Jamaica Plain, designed by the architectural firm of McLaughlin & Burr and built in 1931 and named by Mayor Curley in memory of his beloved wife.

-

- The Home for Aged Couples, 409 and 419 Walnut Avenue, and 2055 Columbus Avenue

The Home for Aged Couples emerged out of a late 19th century charitable movement that sought protection for the aged, the Home for Aged Couples was unique in both supporting the elderly and keeping couples together in their final years. Founded in 1884, the Home for Aged Couples offered long-term care for elderly couples of limited means. In exchange for assigning their remaining assets to the Society, residents were provided with food, clothing, a small weekly spending allowance, and medical care.

It began on Shawmut Avenue in Boston’s South End, but by 1887, the organization relocated to the former estate of Edward E. Rice on Walnut Avenue in Jamaica Plain. Rice, a local merchant and philanthropist, conveyed his property to the Home for Aged Couples along with a $17,000 loan in April of 1887. Located on a 128,000 square foot parcel across Walnut Avenue from Franklin Park the Home offered its residents spaciousness of its own grounds and the proximity of Franklin Park contributed greatly to the tranquility of an aging couple’s final years. The former Rice home served for eight years as the only building on the campus of the Home for Aged Couples. It expanded to include three large buildings designed expressly for the purposes of the institution between 1892 and 1927. Where a single building initially accommodated

residential, dining, and medical care functions, the expanded facilities allowed for the separation of these services.

The Home for Aged Couples thrived through the first half of the 20″” century. However, as additional elderly care resources became available, the number of residents of the Home for Aged Couples dwindled. Perhaps sensing impending decline, the administration enacted a new policy that admitted single men and women to the Home. Reflecting this change, the Home for Aged Couples became the Elizabeth Carleton House in 1955, named for the institution’s founding doctor. Today the campus is preserved and is operated by Rogerson Communities, with continued focus on end of life care.

There are undoubtedly thousands of great Boston love stories waiting to be told. In this historic city, we can only wish our walls could talk!