July 30, 2020 10 Places that Tell the Story of Boston’s History of Resilience (Part 1)

If past is prologue, Boston history gives us some perspective on civic resiliency in the face of crises and opportunities. We took a look around the city to identify places that help to tell the story of how Bostonians of the past responded to public health crises, fires, and the changing needs of Boston’s people. The Covid-19 pandemic and redoubled efforts to address institutional racism have brought into high relief the question of how prepared our community is to respond to immediate disasters, evolving crises and the demands of social change.

We’ve created a list of 10 places that highlight Boston’s resilience (though we acknowledge there are many others) that express our civic strength and expose our weaknesses. We hope you’ll share with us other historic places that express Boston’s adaptation to change! Join us next month for part two.

1. Frederick Douglas Square Historic District, Lower Roxbury

Between 1860 and 1880, Boston’s population more than doubled with the arrival of new waves of European immigrants and municipal mergers with adjacent towns. Poor immigrant workers were often lodged in over-crowded, low standard tenement housing, conditions that fostered unhealthy environments for people, especially children.

Philanthropist and social reformer Robert Treat Paine, Jr. was among many private citizens of means who wanted “better homes for the masses of plain people.” Beginning in 1886, Paine built more than 200 home ownership units on Hammond Street, Cabot Street, Windsor Street, and Westminster Street, on former marshland in Lower Roxbury. His plan featured wide streets and sidewalks, and architect-designed buildings that were made available to the working poor for $2,500 each. With a deposit of $1,000, Paine gave each buyer a 5% mortgage on the $1,500 balance, payable over five years. Today it is known as the Frederick Douglass Square Historic District, and has been home to predominantly African-American families for much of the last century. Nearly 80 of the original houses survive.

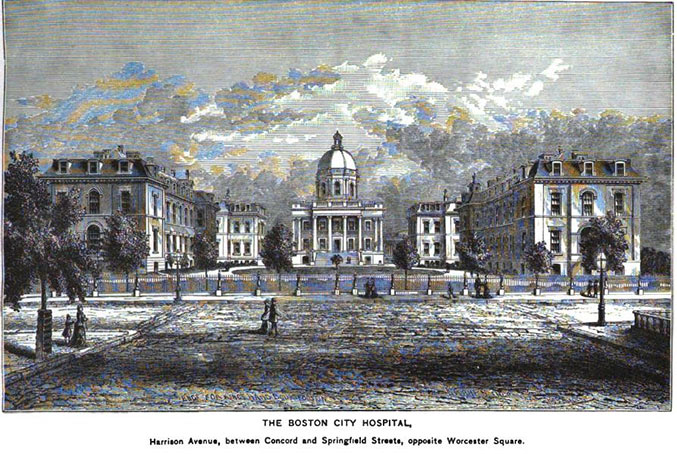

2. Boston City Hospital, Harrison Avenue at Worcester Square

A center for medical innovations, Boston was also a growing metropolis in the 19th century when a massive influx of migrants and immigrants, many of whom were poor, at risk of diseases like cholera, typhoid and dysentery. Boston City Hospital (BCH) opened in 1864 and was the first municipal hospital established in the United States. Much of the original campus has been altered or lost, but segments of early buildings have been preserved along Harrison Avenue. Although the hospital merged with Boston University Medical School in 1996 to become Boston Medical Center, it maintains a distinguished research facility in partnership with Harvard Medical School, and strength in infectious disease investigations, while also continuing its mission of serving the neediest residents of the city.

3. The Grove Hall Welfare Office (Mother Caroline Academy), 515 Blue Hill Avenue

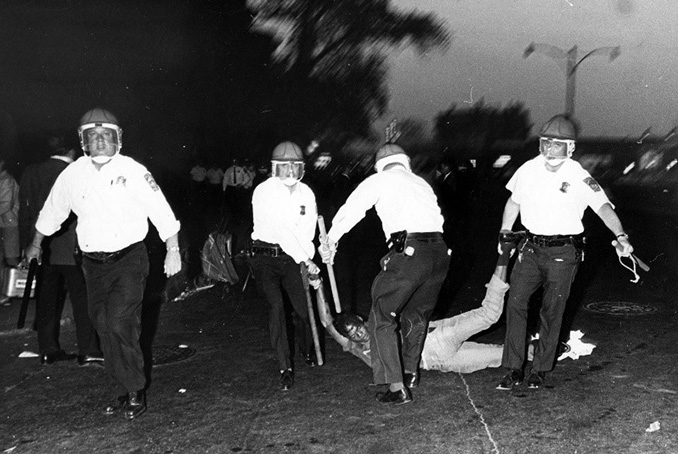

After several years attempting to change the discriminatory treatment of black women in dispensing public welfare benefits, a group of 30 women, organized as Mothers for Adequate Welfare, peacefully occupied the City’s welfare offices in Grove Hall on Thursday, June 1, 1967. They chained the doors to the welfare offices and staged an overnight sit-in that, by Friday June 2nd, had broadened to about 50 people, including men and children. Around the building, more than 200 people had gathered in support of the women. Mothers for Adequate Welfare made a list of demands directly to the director of the welfare office, but no agreement was reached before the police arrived, breaking down the doors, and aggressively removing the women.

The police’s moves generated protests from the surrounding crowd which immediately turned violent. Over the next three days, crowds threw rocks, set cars ablaze and smashed storefronts, devastating the businesses in Grove Hall. By Monday, the violence had ended and clean up began. Welfare reforms were few and came very slowly, but the activism of the Roxbury mothers shed light on the deep iniquities in Boston’s black community, and bolstered the coming decades’ fights for better schools, jobs, good wages, and fairness in the law.

The City no longer dispenses welfare benefits. The welfare building in Grove Hall is now the home of Mother Caroline Academy, a tuition free school for girls in grades 4 to 8.

4. The former location of Fenway Community Health Center, 16 Haviland St.

The first diagnosis of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS was made at the Fenway Community Health Center in 1981. By 1983 Boston’s AIDS Action Committee was founded as a committee of the Health Center, eventually becoming an independent organization by 1986. AIDS Action is the oldest and largest organization in New England dedicated to helping people with AIDS and HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) and their families and friends through education, advocacy, fundraising (the annual Larry Kessler AIDS Walk) and public policy development.

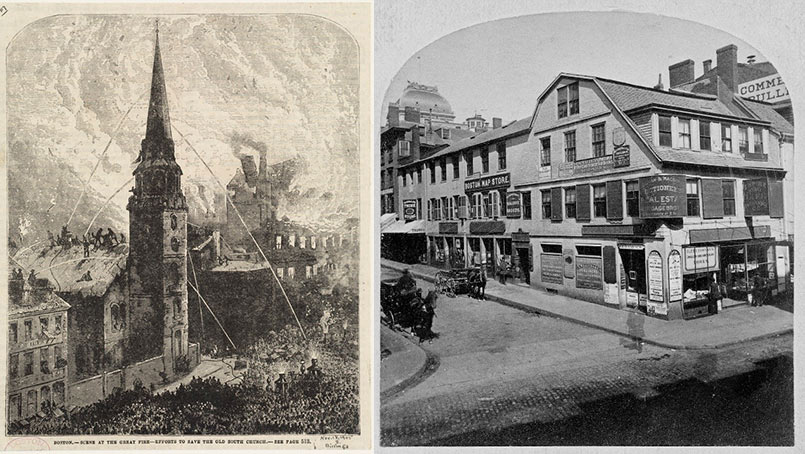

5. The Old Corner Bookstore (3 School Street), the Old South Meetinghouse (310 Washington Street) and the Great Fires of Boston

The Old Corner Bookstore and the Old South Meetinghouse are sites on Boston’s Freedom Trail and known for their historical roles in Boston’s literary and revolutionary histories. However, both also stand as examples of Boston’s resiliency in the face of major disasters – the Great Fire of 1711 and the Great Fire of 1872. The 1711 fire destroyed much of the area from today’s State Street to School Street, including the wood frame house built for puritan reformer Anne Hutchinson which sat on the site of today’s Old Corner Bookstore. Dr. Thomas Crease’s new home and business, built there in 1718, became of one of the earliest examples of a brick residence in Boston. It wasn’t until the mid-19th century that the building became the famed publishing house of Ticknor and Fields.

In 1872, the Great Fire of Boston swept through most of today’s downtown and financial district over twelve hours, destroying 65 acres of downtown and 776 buildings, and killing 30 people. It caused 73.5 million in damage (over $1.5 billion in today’s dollars). Only the focused attention of a fire unit from Portsmouth NH on the Old South Meetinghouse saved the structure in the last few hours of the fire.

In 1876, the Old South Meetinghouse became the region’s first great preservation story when it was saved from demolition by a group of women who bought it for a museum. In 1960, the Old Corner Bookstore was bought by Historic Boston Inc. to save it from demolition for a parking garage.

We hope you’ll share with us other historic places that express Boston’s adaptation to change! Join us next month for part two.