21 Sep How Roxbury’s Ionic Hall and St. Luke’s Chapel became the Church of St. John St. James

A special thanks to Jeff Gonyeau for writing this history of St. John and St. James for our blog.

The group of buildings on the northern edge of Roxbury’s John Eliot Square now known as St. John’s / St. James Episcopal Church represents the complex history and relationship between several prominent institutions and two historically significant structures. While the juxtaposition of this Federal Period house and Gothic Revival chapel seems a bit mysterious, the history of the evolving uses of this site, and its close relationship to the Episcopal Church, explains how this intriguing campus came to be and suggests clues as to how the celebrated architect Ralph Adams Cram created a gem of a chapel for Roxbury.

Ionic Hall—the imposing brick mansion fronting on Eliot Square—was constructed between 1800 and 1804. This was a busy time in the Square, as the First Church of Roxbury’s elegant meetinghouse directly across Roxbury Street (their 5th meetinghouse on this site) was also getting underway; in fact, members of First Church met in the house for a time while their meetinghouse was under construction, and before the house was complete. Built by a Captain Stoddard of Hingham as a home for his daughter, Sally Hammond, the house remained a residence through most of the 19th century, when it had several prominent occupants. During its time as a residence it received various expansions and enhancements, including its distinctive columned portico (whose Ionic columns seem to lend the building its name) along with a full third story and attic with dormer windows.

The house’s transition to an institutional use began in 1876, when the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts purchased it and located St. Luke’s Convalescent Home there. Founded in 1870, St. Luke’s Home “was for women needing a place to recover after leaving the hospital and before returning home, or for women who simply needed to rest for a short time away from their home environment,” as noted in a 1984 history of the diocese. (The word “Consumptives” sometimes appears in place of “Convalescents” in the name of the Home, but this seems to be an error, as the Episcopal diocesan records consistently use the latter.) The Home was served for a short time by the Sisters of St. Luke, a (short-lived) monastic sisterhood of Episcopal nuns established within the diocese in 1870 specifically to staff the home.

Eventually, after a quarter century of operation at the site, the Home decided that its residents needed a proper building in which to attend to their spiritual needs and to support their physical recovery. The original building permit for their new chapel still exists. Dated October 18, 1901, it indicates that the St. Luke’s Home Corporation planned to construct a 34’ by 47’ brick and stone chapel (with a copper roof and cornice) designed by Boston architects Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson and to be built by H.P. Cummings, Inc. of Ware, MA, for an estimated cost of $10,000.

Although it was to be small in size, the Home’s leadership had selected an architect with a growing reputation to design its new building. By 1901, Ralph Adams Cram (1863-1942) had already made a splash locally with his design for All Saints’ Church in the Ashmont section of Dorchester. Begun in 1892, All Saints’ was Cram’s first major commission and its success soon led to several other church commissions for Cram in eastern Massachusetts and eventually around the country; All Saints’ design also inspired many other architects and is said to be the origin of the “Modern Gothic” style that came to dominate much church building in America during the first half of the 20th century.

Although he was the son of a Unitarian minister, in his early 20’s Cram embraced the high-church or “Anglo-Catholic” wing of the Anglican (Episcopal) Church and made many connections in the small but vital Anglo-Catholic community in greater Boston. Founding monastic communities for men and women (based on medieval Roman Catholic institutions) in England and America became an Anglo-Catholic pursuit in the mid-19th century. These include the Society of St. John the Evangelist (founded in Oxford, England, in 1866 and whose monks came to Boston in 1870; their Cram-designed monastery from the late-1930s on the Charles River outside of Harvard Square is one of hist last personal designs) and the Society of St. Margaret (founded as a nursing order of nuns in Sussex, England, in 1855 who came to Boston in 1873 to act as superintendents at Children’s Hospital; their convent was on Fort Hill in Roxbury for most of the 20th century, until they moved to their former summer retreat in Duxbury in recent years). The establishment of the St. Luke’s Home for Convalescents in 1870 can be seen as part of this wider movement, and Cram’s sympathy with and connection to the Anglican religious orders may have helped make him and obvious candidate for the St. Luke’s Chapel commission.

(As a bit of a digression, and to further illustrate these connections, Cram’s mentor, the English architect Henry Vaughan, designed the Sisters of St. Margaret’s first chapel on Beacon Hill. Mary Lothrop Peabody, who lost her only daughter in early childhood, was deeply supportive of the Sisters of St. Margaret’s work at Children’s Hospital and served on its board. Mrs. Peabody, like Cram, was the child of a Unitarian minister (the Rev. Samuel Kirkland Lothrop, minister of the Brattle Square Church, which built the H.H. Richardson-designed church on the corner of Commonwealth Ave. and Clarendon Street now home to First Baptist Church of Boston). Also like Cram, she had a conversion experience and became an ardent Anglo-Catholic. Mrs. Peabody and her husband, Col. Oliver White Peabody, became the major donors to build Cram’s first major building—All Saints’, Ashmont, just a few miles north of their country estate in Milton—and may have had a hand in delivering this commission to Cram.)

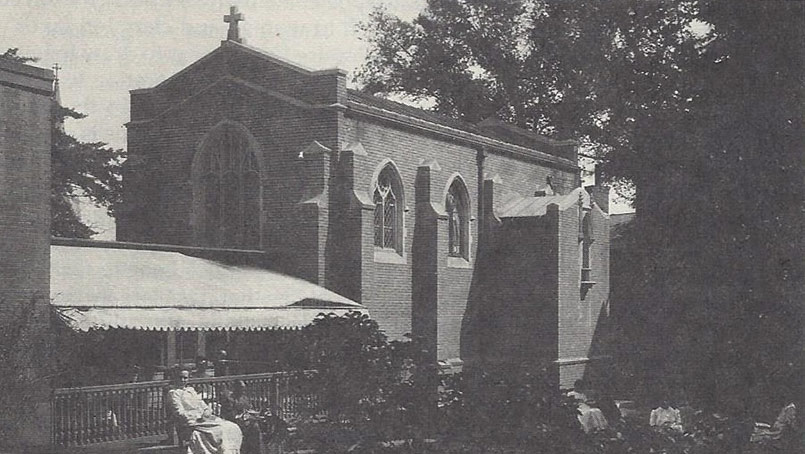

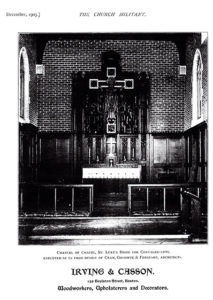

The entrance to St. Luke’s Chapel faces west (with the altar inside at the other end of the building facing to the east, a traditional liturgical orientation) into the sidewall of Ionic Hall, diminishing its presence somewhat along Roxbury Street. However, while its scale is modest and the design of its brick and limestone exterior is restrained, as was the case with his larger religious buildings, Cram pulled together a team of talented craftspeople in many media to fit out and embellish the interior with elegant furnishings and liturgical fittings designed by his firm. Most notably in St. Luke’s is the wooden reredos (the tall carved paneling behind the high altar) and other paneling in the chancel area around the altar, which was executed by Irving and Casson (Boston-based cabinet makers and wood carvers who, especially through their Cram connection, developed a particular expertise in Gothic Revival church interiors), with figural carvings by the famous Boston-based Bavarian wood carver whose career Cram cultivated, Johannes Kirchmayer. The massive carved “Christus Rex” crucifix of the reredos—on which Christ is represented reigning in majesty rather than suffering the agony of the cross, which was an optimistic theological representation that Cram often used—dominates the interior of the chapel. The elegant stone baptismal font, carved by John Evans, originally included tall, sculptural bronze font cover that Cram commissioned by sculptor Henry Wilson. Even in such a small space, Cram created a compelling environment full of the finest liturgical art that must have been a source of spiritual comfort to the inhabitants of the Home. A historic photo showing several women relaxing on the lawn in front of a now demolished covered passageway that was built to connect the chapel with Ionic Hall captures the restful environment of the Home.

So—how did St. Luke’s Home become the Church of St. John/St. James? St. John’s and St. James’ were once independent Episcopal parishes in Roxbury. In fact, St. James’s, organized in 1832, was the first Episcopal parish in Roxbury, and one of the earlier Boston-area parishes of the diocese. Its church building, attributed to architect Richard Upjohn, was located on St. James Street near Washington Street. St. James’s embraced the Anglo-Catholic high church movement (Cram designed a new baptistry for their Upjohn church in 1902), and developed a strong missionary tradition, helping to establish other new parishes. One of these was St. John’s, which began as a chapel on Tremont Street in the 1860s and was organized as a parish in 1872 with a building at 1262 Tremont Street in Roxbury Crossing.

The second half of the 20th century brought major changes to the Ionic Hall/St. Luke’s site, and to the Roxbury neighborhood in general. By the late 1960s, St. Luke’s Home was struggling to conform with regulations governing the running of modern nursing homes, and eventually combined with other institutions to establish what is now known as Sherrill House in a new location.

Also in the 1960s, responding to the changing demographics of the neighborhood, St. John’s had become a predominantly African American congregation. In 1967, St. John’s church was destroyed by a fire, and the congregation was not allowed to rebuild on their site due to the planned construction of the Inner Belt highway along Tremont Street. Instead, the congregation purchased the former St. Luke’s Home buildings for $70,000 to serve as the location for their church. According to the 1984 history of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, “while St. John’s continued to prosper in numbers by reaching out to the black population of Roxbury, St. James’s Parish was hard hit by the post-World War II exodus of the white population. In 1962, [the parish’s] church building was razed as part of ‘urban renewal.’” The remaining members of St. James’s continued to meet separately after their church was demolished until 1968, when the two parishes “came to recognize the value of combining their resources” and merged as the new Church of St John/St. James. The new parish began worshiping on the former St. Luke’s site in a modern addition to the Ionic Hall building, while occasionally using St. Luke’s Chapel for special services and ceremonial occasions. This is the arrangement that largely continues to this day.

While St. John’s/St. James’s remains an active congregation, both Ionic Hall and St. Luke’s Chapel are in need of creative efforts to solve the buildings’ deferred maintenance needs, to find ways to fully activate this prominent site in Roxbury’s John Eliot Square, and to preserve these important historic resources. HBI is working with the Episcopal Diocese to redevelop the building so that it may once again be used by its congregation and its neighbors.