13 Dec An Old Corner window into the Boston Tea Party

As the 250th anniversary of the Boston Tea Party approaches on December 16th, Historic Boston wondered what the residents of the Old Corner Bookstore would have seen from their windows on that fateful night in 1773 when a massive crowd of Bostonians protest the English government’s imposition of new taxes and importing restrictions on tea on the streets around the Old South Meeting House. By the end of the evening, a group of colonists — some dressed as Native Americans — would board three British ships in Boston Harbor and toss contentious shipments of tea into the Harbor at Griffin’s Wharf.

In 1773, the 1729 Old South Meeting House was Boston’s largest gathering space. It became the central meeting place for discussions and protests around what to do with a large tea shipment that had arrived in Boston in November, but could not be unloaded due to colonists’ opposition to the English government’s new Tea Tax and a monopoly on tea shipments recently given to the East India Company. As the December 17th deadline for the unloading of the tea and paying the necessary taxes arrived, more than 500 Bostonians met in and around at the Old South Meeting House in protest. More than 5000 people gathered on the streets around the meeting house to oppose the new tariffs and the arrival of the tea shipments.

In 1773, the building we now call the Old Corner Bookstore was already over 50 years old. Built in 1718 by Thomas Crease to house his apothecary shop with residence above, by 1773 it had changed ownership twice and was owned by the estate of Thomas Palmer, which had purchased the property in 1753 for Palmer’s minor children. It’s not known who the shop tenants were or who lived upstairs on the evening the Tea Party took place, and we know nothing about the residents’ political leanings. Were they loyalists who supported England’s right to tax the colonists, or did they support the rebellion? Whatever their views, they would likely have become accustomed to living in a neighborhood active with revolutionary fervor, as many public meetings were held at the Old South Meeting House in response to tensions between the British government and Bostonians over sovereignity and colonial rights.

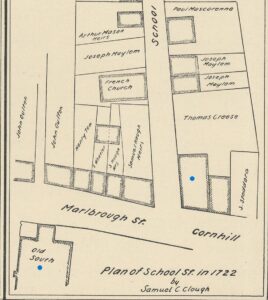

We also don’t know exactly how this corner of Boston appeared at that time, but maps from the period and subsequent conjectures help shed light on the relationship of the two suviving colonial buildings to each other. Nineteenth century historian Samuel Clough re-created a map that shows his interpretation of the neighborhood in 1722 , with Thomas Crease’s house (today’s Old Corner Bookstore) on the corner of School Street and Cornhill Street (now Washington). Diagonally across the street is the Meeting House, labeled “Old South” on the map. The meetinghouse we know today was not built until 1729, but an earlier structure sat on this site beginning in the 1660s. Clough’s map shows several small buildings across from the Meeting House. Were they timber or masonry, shops or residences? The map doesn’t say.

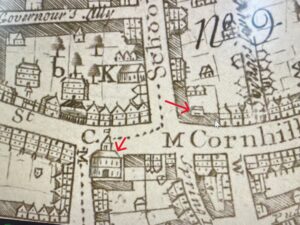

However, a contemporaneous map by William Price from 1743 is more illustrative. The Meeting House we know today had been built, and while the proportions of the Old Corner Bookstore building are out of scale, the map suggests a view corridor between the two buildings that continues today. The map also tells us that all other buildings were two and three story structures, guaranteeing that the occupants of the bookstore building would minimally have been able to see the meetinghouse steeple and the thousands of people on the streets that night — thought to have represented at least a third of Boston’s population of 16,000 people.

On the heels of rousing speeches within and outside the Old South Meeting House, between 30 and 130 colonists surreptitiously dumped 342 chests of tea from three East India Company ships at Griffins Wharf into Boston Harbor, marking one of the most dramatic and economically provocative events leading up to American Independence.

The Old Corner Bookstore’s 306-year history is rich, with much of its celebrity centered on its 19th century literary history. But if walls could talk, this building would likely also have a lot to say about what happened on the streets of this neighborhood in the years leading up to the American Revolution.