March 5, 2019 Louisa May Alcott’s Pot of Gold

Kit Haggard is the Director of the Boston Literary District – a collection of 87 historically significant literary sites spread throughout Boston’s Downtown, Back Bay, Beacon Hill, Theater, and South End neighborhoods. Kit earned her BA from Sarah Lawrence and her MFA from Emerson College. Her fiction has appeared or is forthcoming in The Kenyon Review, Prairie Schooner, Electric Literature, and The Masters Review, among other places; critical essays on queer literature and fabulism have appeared in a number of outlets. Kit is the recipient of the St. Botolph Emerging Artists Award, the Rex Warner Prize, and the Nancy Lynn Schwartz Prize for Fiction. She teaches writing at Emerson College and GrubStreet. Kit was recently featured on the City of Boston’s Boston Uncovered to speak about the Edgar Allen Poe statue near the Boston Public Gardens. Kit’s blog post explores the rise of Louisa May Alcott from her days as a humble school teacher to her meteoric literary success, featuring a sassy letter she wrote to James T. Fields of the publishing house Ticknor and Fields.

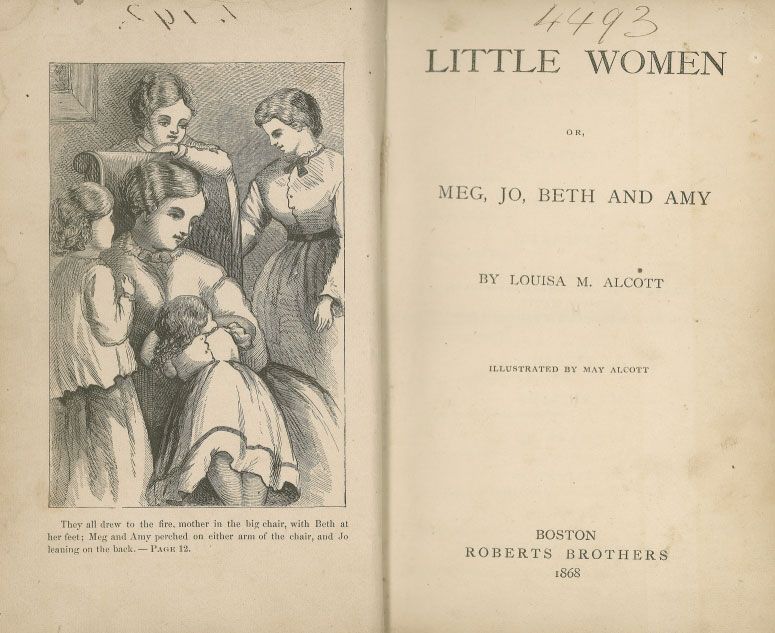

This November, Greta Gerwig wrapped filming of her new adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, which reportedly focuses less on the childhood of the titular little women and more on their young adulthood. Saoirse Ronan will play Jo March, with Florence Pugh, Eliza Scanlen, Emma Watson, Laura Dern, and Meryl Streep playing the other March sisters, their mother, and Aunt March, respectively.

Gerwig seems interested in remaining close to Alcott’s own history, shooting in Concord and the Arnold Arboretum and, most importantly, in Boston.

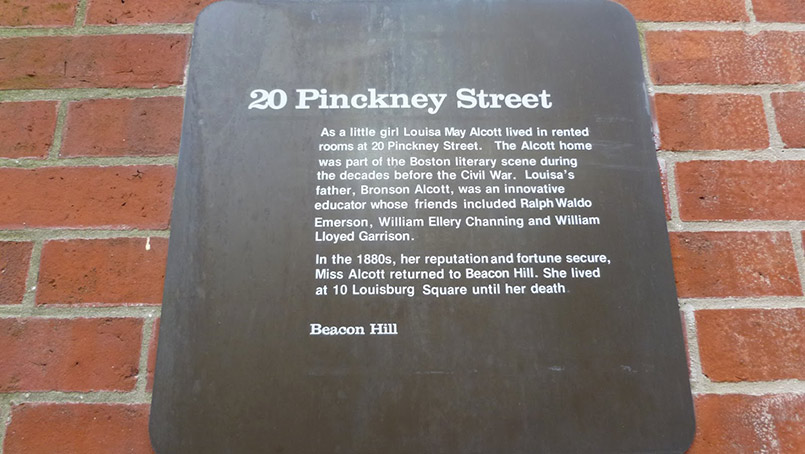

Though Louisa May Alcott is most often associated with Concord and with the family home, Orchard House, the Alcotts lived at several locations in Boston, two of which we recognize in the Boston Literary District: 20 Pinckney Street, where the Alcotts were living when Louisa May’s first story was accepted; and 10 Louisburg Square, a Greek Revival home built in 1880, which she purchased in 1882 and occupied until her death in 1888. Today, both are private residences, which retain something of the secluded charm they must have had when Alcott lived in them.

Other pieces of Alcott history are everywhere in the Boston Literary District: Bronson Alcott ran the Temple School on Tremont Street–at which Margaret Fuller (resident of 486 Washington Street) was a teacher–and would have visited with the Saturday Club at the Omni Parker House; Little, Brown (34 Beacon Street) was an early publisher of Louisa May; as was Gleason’s Pictorial (101 Tremont Street); Alcott would have visited King’s Chapel, the Common, and the Boston Athenaeum.

With these new adaptations, I always have to hope that new generations of readers will be encouraged to seek out this history. Though the story of Jo, Meg, Beth, and Amy is a fiction, it is a fiction based on the real lives of Louisa, Anna, Elizabeth, and May, and the world they inhabited has not entirely vanished. It’s visible in places like Beacon Hill, where one can imagine the poor though boisterous Alcott family squeezed into their apartments at 20 Pinckney Street; it’s palpable at 10 Louisburg Square, where I picture a more somber Louisa May, caring for her father following his stroke, neither entirely recovered from the loss of two of Louisa May’s sisters and her mother. These places are easy to find, if you’re willing to look.

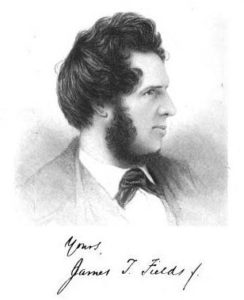

Despite the success and popularity of Little Women today, I wanted to tell the unlikely story of how it was written and published, which includes some of my favorite writing by Alcott: a two line letter she sent to publisher James T. Fields in 1871.

In the mid 1850s and into 1860s, when Louisa May Alcott was in her twenties, she was working as a teacher in Boston to help support her family. Her father, Bronson Alcott, was an idealistic school reformer, and her mother, Abigail Alcott (née May, the middle name she gave to Louisa and her youngest daughter), was a social worker, abolitionist, and partner in many of Bronson’s failed projects. As a result, the family lived in almost perpetual poverty, and Louisa May in particular felt pressure to help the family make ends meet.

Her ambition, however, was to become a writer, a creative outlet she used to both escape from and process her circumstances. A few of her short stories and poems had been published in periodicals and women’s magazines. A book of her stories, Flowers Fables–which she had written for Ralph Waldo Emerson’s daughter, Ellen–had recently been published to some success, but she only received $35 for the manuscript (just over $1,000 in today’s terms). She was unable to earn enough money to quit her other positions and write full time.

In this period, Alcott wrote a story entitled “How I Went Out to Service,” which was loosely based on the seven weeks during which she worked as a servant and companion for a gravely ill woman and her elderly father. In her journal, she wrote of this period, “I go to Dedham as a servant & try it for a month, but get starved & frozen & give it up.”

Shortly after, in 1862, Alcott lived briefly with her second cousin, Annie Adams. Adams was a writer herself, author of a number of “sentimentalist” novels as well as sketches of the many literary figures in her life, including Longfellow, Emerson, and Hawthorne; in later years was the close companion and, it is suspected, the lover of American novelist Sarah Orne Jewett. At the time when Alcott stayed with her, however, she was married to publisher and editor James T. Fields.

Fields is known today as one half of Ticknor & Fields, the publishing duo that began in the Old Corner Bookstore. Fields had been employed by Carter & Hendee, the first of almost a century of publishers to occupy the building; when Carter & Hendee sold the space to William Davis Ticknor and John Allen, Fields stayed on. John Allen eventually left the firm, and after several name changes, Ticknor & Fields was born. William Ticknor handled the business end of the publishing outfit, but Fields was known as the literary and creative engine. In 1861, the two purchased The Atlantic Monthly, and Fields replaced James Russell Lowell as editor.

At some point during the period in which Alcott was staying with Adams and Fields, she showed him her story, “How I Went Out to Service,” with the hope of seeing it in The Atlantic Monthly. Fields famously advised Alcott, “Stick to your teaching; you can’t write.” He gave Alcott $40 to support the kindergarten she had recently opened, suggesting that she could repay the loan when she made a “pot of gold.”

The kindergarten was ultimately short lived, but nothing could have galvanized her more. In her journal, she wrote, “I won’t teach; and I can write, and I’ll prove it.” And in fact, she did see several pieces appear in The Atlantic Monthly.

The beginning of her real success, however, was a series of letters she wrote home during the time she spent as a nurse during the Civil War, what was later collected as Hospital Sketches. Following a bout of typhoid, she left the war and wrote a number of novels–under her own name and a pen name–which saw moderate success.

Perhaps because of this, she believed that her work for younger readers would never be as successful as the novels intended for adults. In the late 1860s, publisher Thomas Niles tried to convince Alcott to write a book for girls, but the project seemed to stall out for her. She was finally inspired to finish it only when Niles promised to publish the latest work by her father on the condition that Louisa May write her juvenile novel as well. She wrote over 400 pages in two months–the novel that would become Little Women.

Little Women was ultimately heavily influenced by the Alcotts’ life. The May family became the March family–a more difficult and tempestuous month. Louisa, who had often gone by the tomboyish “Lu” became Jo; Anna, Elizabeth, and May became Meg, Beth, and Amy.

Like the March girls, the Alcotts were raised in a small house in Concord. Bronson Alcott moved his family out of the city following the failure of his Temple School, which was closed largely due to a scandal around Bronson’s belief in sex education. After renting a cottage for some years, the family moved to a utopian vegetarian commune called Fruitlands. Following the failure of that experiment, the family moved a few more times before settling at Orchard House, the basis for the setting of Little Women.

The novel was an immediate success and lifted the Alcotts out of the poverty that Louisa May had described. Perhaps most satisfyingly, a few years after the publication of Little Women, Alcott wrote to James Fields who had rejected her not so many years before, saying “Once upon a time you lent me forty dollars, kindly saying that I might return them when I made ‘a pot of gold.’ As the miracle has been unexpectedly wrought I wish to fulfill my part of the bargain, & herewith repay my debt with many thanks.”