07 Feb 2020 Modernist in Boston: The Work of Artist Jack Levine

Born in 1915 to Lithuanian immigrants, renowned artist Jack Levine grew up in Roxbury during the early 20th century, a neighborhood that exemplified the American melting pot of Jewish Eastern European, German, and Irish settlers. In his years as a professional artist, Levine earned a reputation for his biting art, which was particularly critical of politicians, high society, and police officers.

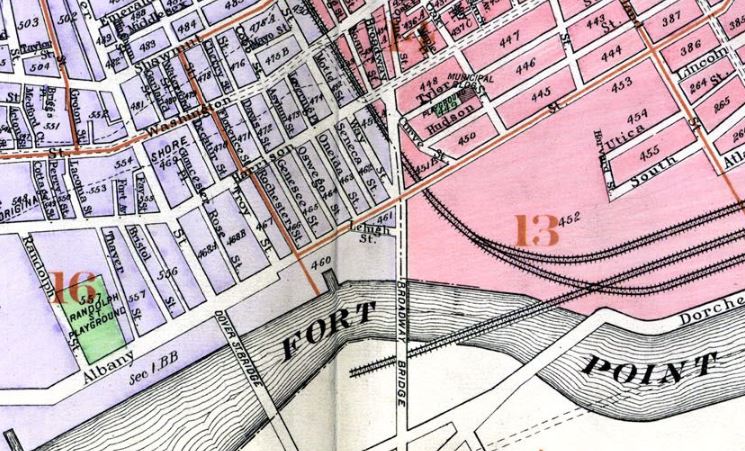

For the majority of his childhood, Levine’s lived in a tenement on Rose Street, off Harrison and Dover Street, which Levine later compared to Los Angeles’ skid row. Despite his bleak description, in an interview, Levine remembers his mother Mary encouraged his artistic pursuits from an early age, supplying him with a steady stream of pencils, crayons, and paper. According to Levine, Mary spent a lot of her time in the kitchen (reportedly making lunches for bootleggers in the neighborhood during the Great Depression), and she allowed him to keep his art supplies in the cool oven during summer months when she wasn’t using it. Levine studied drawing at the Jewish Welfare Center in Roxbury, under Harold K Zimmerman from 1924 to 1931 and later took painting classes at Harvard University (1929 to 1933), where he studied under Denman W. Ross. At an early age, he was practiced at recording his surroundings, drawing and sketching events of the urban scene, such as the Great Boston Police Strike of 1919. Levine never graduated from high school or university.

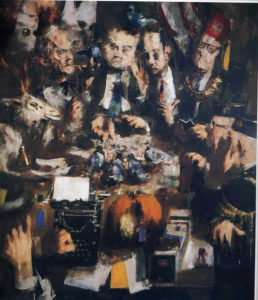

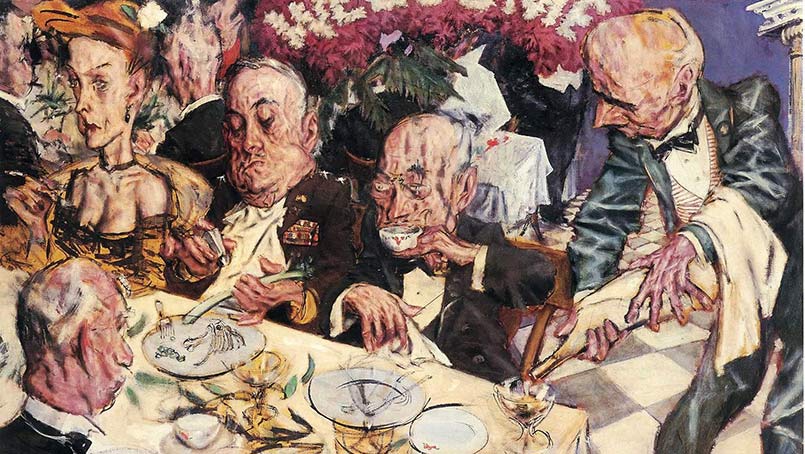

Feast of Pure Reason (1937)

From 1935 to 1940, Levine was employed by the Works Progress Administration, and produced a number of paintings including: Card Game (1933), Brain Trust (1935), and String Quartet (1937). String Quartet was awarded a $3,000 prize by MoMA. One of his most famous painting was The Feast of Pure Reason (1937), a scathing commentary about political corruption. The painting was displayed which was shown at MoMA in New York and was later the title for an hour-long documentary about Levine’s career. In the painting, a Bostonian politician, a police officer and a businessman appear to be conspiring together. The theme of corruption was cause for debate among the MoMA board members, who questioned if the piece should be exhibited.

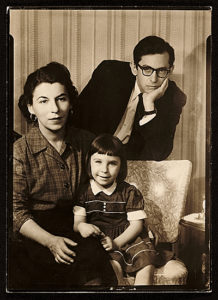

In 1939, the sudden death of Levine’s father caused a marked change in the subject matter of his work, prompting a series of paintings of religious Jewish scenes. Much of his later work explored religious scenes like David and Saul (1989) and Cain and Abel (1961), which was purchased by the Vatican in 1973 at the pleasure of Pope Paul VI. In an interview, Levine laments he never painted images of his mother or father. However, he created portraits of his wife and fellow artist, Ruth Gikow, and his daughter Susanna throughout his career. Through the 1950s, Levine’s work continued its harsh criticism of American life, as exemplified by his paintings Election Night (1954), Inauguration (1958), and Thirty- Five Minutes from Times Square (1956).

Welcome Home (1947)

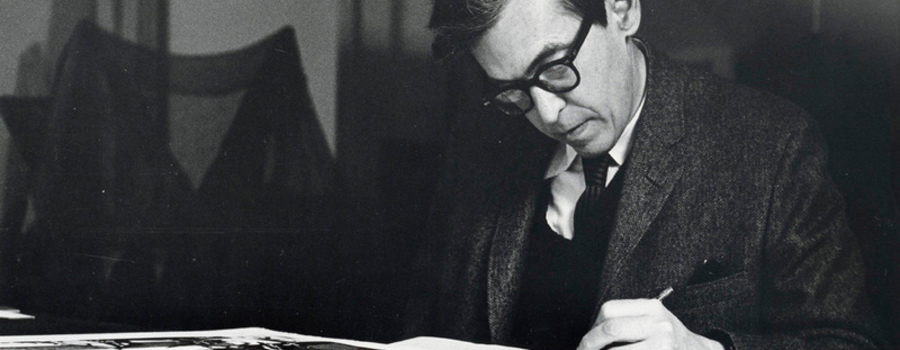

After a stint with the US Army as a camouflage painter, Levine was awarded a Fulbright grant to travel to Europe. The travel influenced Levine’s work deeply, which particularly reflected the work of the Old Masters of Mannerism, namely El Greco’s distorted, twisting shapes. The exaggerated images and figures heightened the satire of Levine’s paintings, which were met with heavy criticism. When one of Levine’s early paintings, Welcome Home (1946), was in included in an exhibition of American culture in Moscow in 1959, he was investigated by the chairman of the House Committee on Un-American Activities. President Dwight D. Eisenhower even remarked on the piece saying that, “It looks more like a lampoon than art, as far as I am concerned.”

Levine described his warped style as a statement. The grotesque figures in his paintings were purposeful and, “I felt from my early days that good and bad weren’t simply aesthetic questions,” he told American Artist magazine in 1985. “You have to defend the innocent and flay the guilty.” Levine never identified himself with one artistic movement, “I am alienated from all of these movements. They offer me nothing. I think of myself as a dramatist. I look for a dramatic situation, which may or may not reflect some current political social response.” In the 1960s and 70s, Levine’s work clung to abstraction and the avant-garde, best exemplified in paintings like The Gangster Funeral (1965) and Panethnikon (1978). Levine’s work was exhibited in museums around the New England area including The Museum of Modern Art in New York, Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston in 1952, and at the Jewish Museum in New York in 1978.

Levine once said of himself that, “I am primarily concerned with the condition of man.” His extensive oeuvre socially-conscious art demonstrates how he perceived the strengths and weaknesses of society, never shying away from shining a light on the underbelly of his fellow man. Levine died in his Manhattan home at the age of 95.