28 Oct 2024 “Now talk we of graves and goblins”: Hawthorne’s spooky tales immerse readers in MA history

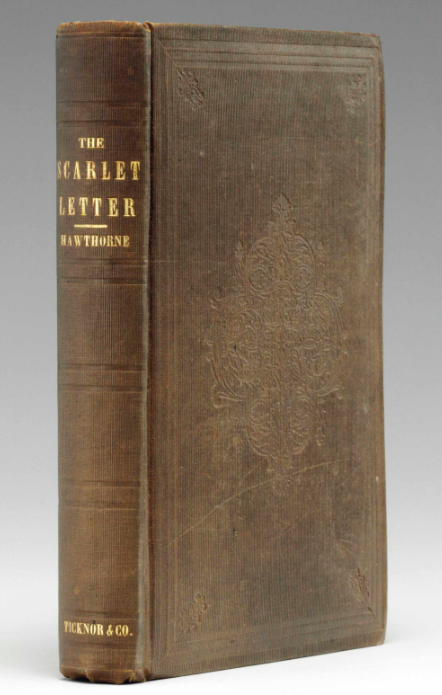

Looking for a fright this spooky season? Look no further than the works of Nathaniel Hawthorne, a favorite author of esteemed Old Corner Bookstore publisher’s Ticknor and Fields. Hawthorne sets his stories around Massachusetts and occasionally the far corners of New Hampshire (Check out “The Ambitious Guest” here), with a haunting lens for local readers to experience these places we know well but with a fresh and foreboding perspective that only Hawthorne can provide.

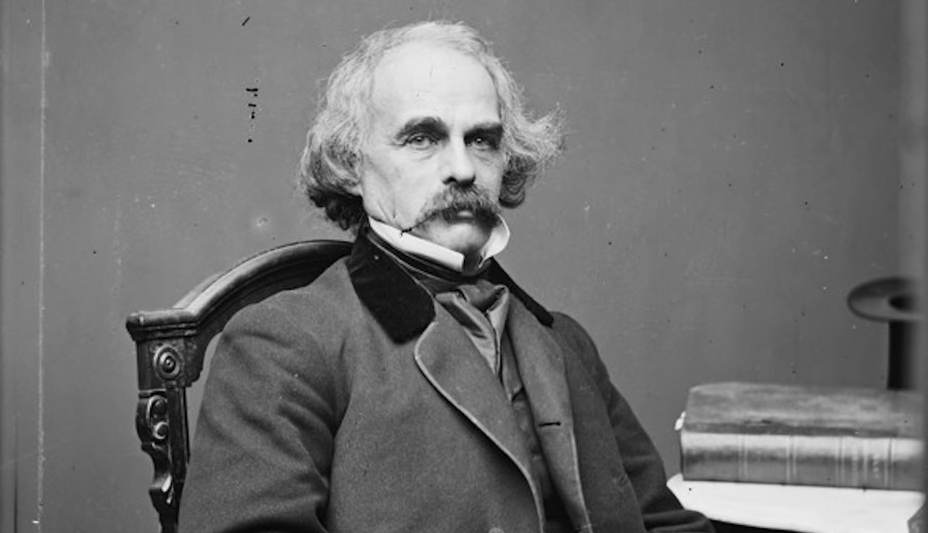

Born in Salem, MA on July 4, 1804, Hawthorne is a product of Puritan settler colonial America, but in the most satisfying and endearing of ways. Hawthorne’s works were deeply contemplative of the human condition, psychology, and religious conceptions of morality that we impose on our societies. This is illustrated in his most famous work The Scarlet Letter. However, Hawthorne carries that literary exploration of humanity, ethics, and irony so well–known in The Scarlet Letter throughout his short spooky stories as well. Although a brief history of the Ha(w)thorne’s is not needed to enjoy his stories, knowing what and where Hawthorne comes from makes his employment of literary techniques all the more rich and often hint toward where his narratives are going.

Born in Salem, MA on July 4, 1804, Hawthorne is a product of Puritan settler colonial America, but in the most satisfying and endearing of ways. Hawthorne’s works were deeply contemplative of the human condition, psychology, and religious conceptions of morality that we impose on our societies. This is illustrated in his most famous work The Scarlet Letter. However, Hawthorne carries that literary exploration of humanity, ethics, and irony so well–known in The Scarlet Letter throughout his short spooky stories as well. Although a brief history of the Ha(w)thorne’s is not needed to enjoy his stories, knowing what and where Hawthorne comes from makes his employment of literary techniques all the more rich and often hint toward where his narratives are going.

Hawthorne’s ancestor, William Hathorne, was a magistrate in 17th century Salem, whose strict Puritan orthodoxy informed what he was remembered for: the sentencing of Quakers to public whippings. The same Hathorne, would also become a major in the colonial New England Confederation allied against Native Northeastern forces (the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, Narragansett, and Pocumtuck) in King Philip’s War.

William Hathorne’s son was a similarly brutal reflection of Puritan society. John Hathorne had made a name for himself as the “Hanging Judge” for sentencing the 19 victims of the Salem Witch Trials to death in 1692. Nathaniel Hawthorne was well aware of his family history and as the irony of his stories unfold, it is clear he saw his writing as an opportunity for penance and perhaps a redemption of his family name in acknowledging their actions. It is thought that Hawthorne sought to distance himself from the actions of his ancestors when he began writing, for he added the distinctive “w” to his name.

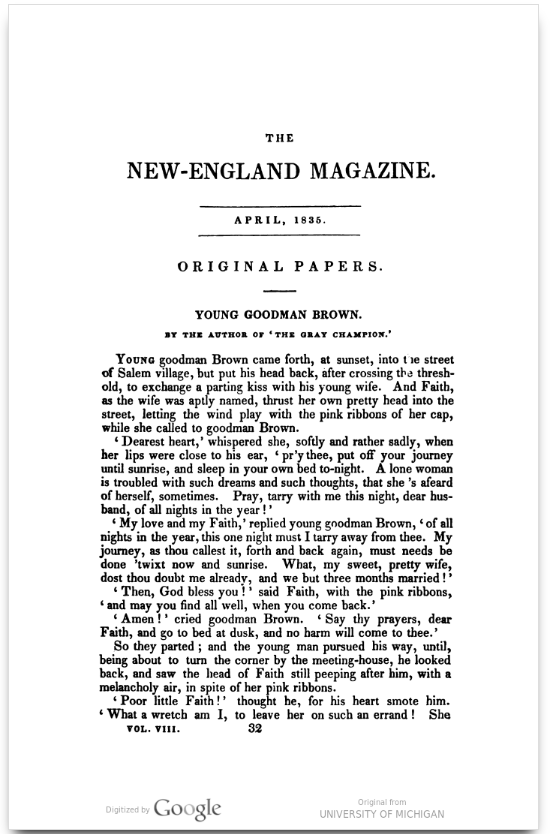

Should you only have time for one story, we would suggest the classic “Young Goodman Brown.” Published in Boston in 1835 by The New-England Magazine (not related to The New England Magazine), from Eastburn’s Press on nearby Washington Street. Hawthorne was not yet writing under his name, but “Young Goodman Brown,” “The Ambitious Guest,” and “Graves and Goblins,” were all published in the same 1835 edition of The New-England Magazine in Boston. Now that you’re familiar with a bit of his family history, a reading of this tale offers a fascinating glimpse into the way Hawthorne processed his family’s history in Massachusetts. Oh, and the devil passes through downtown Boston in this chilling allegory.

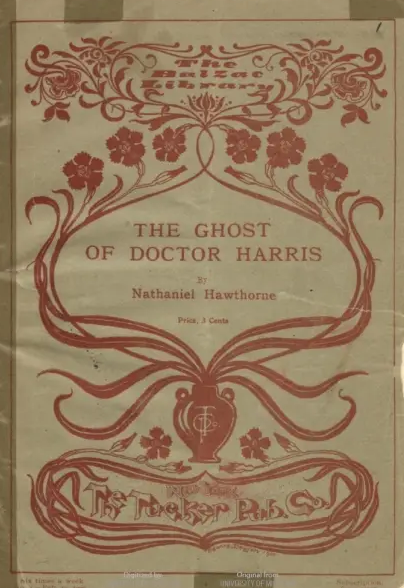

Next, enjoy a real ghost story: “The Ghost of Dr. Harris.” A tale Hawthorne had shared with friends who begged him to write down such a curious occurrence and which was not recognized as among his work until an early 1900s publication resurfaced. Beware– this is not fiction and could change the way you perceive the Boston Athenaeum. (Fret not– this happened at the Athenaeum’s previous location on Pearl Street, not its present location on Beacon Street!)

Then, enjoy “Graves and Goblins”, a story from a ghost stylized by Hawthorne himself, years before his own encounter with Dr. Harris transpired and which offers a window into his personal beliefs concerning what unfinished business souls left to dwell on earth may be doomed to endure.

Finally, read some of Hawthorne’s last and unfinished novel: The Dolliver Romance. James T. Fields, as a pallbearer at his funeral, had fondly placed this partially written manuscript on Hawthorne’s casket in 1864.