January 31, 2022 Older than Stonehenge: Boston moves to protect Native American Quarry in Mattapan

The 7,500-year-old Ryolite quarry of the Massachusett Tribe is closer to being designated a Boston Landmark.

In November, the Dorchester Reporter summarized this unique historic and archeological site in Mattapan as it was nominated to become a protected Boston Landmark.

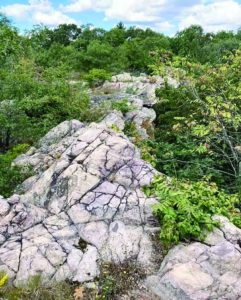

“…[R]arely does the city have an opportunity to place landmark status on a site dating back before the Egyptian pyramids or England’s Stonehenge,” the Reporter noted. “But that is what’s happening at a curious site in a busy urban area behind St. Angela’s Church along Babson and Cookson Streets…. The quarry is the source of an ancient volcanic stone prized for its banded maroon color and ideal qualities for making stone tools. “

At a November Boston Landmarks Commission hearing, Joe Bagley, the City of Boston’s Director of Archaeology and a member of the Landmarks Commission, offered a presentation outlining the historic Mattapan site, quoting the massachusetttribe.org website, and referring to Chickataubut, the Sac’hem, or leader, of the Neponset Band of the Massachusett in 1620:

“The quarries within the Massachusett territory supplied stone, quartz and other minerals for tools, weapons, cellars, ceremony etc. Quarry stone, stone tools and weapons were also valuable trade items. All the valuable resources under Chickataubut’s control did not go unnoticed by rival tribes and raids on the Massachusett fields and resources had to be defended. Chickataubut was often challenged by other tribes from the north and west seeking to take over this valuable territory.”

“The quarries within the Massachusett territory supplied stone, quartz and other minerals for tools, weapons, cellars, ceremony etc. Quarry stone, stone tools and weapons were also valuable trade items. All the valuable resources under Chickataubut’s control did not go unnoticed by rival tribes and raids on the Massachusett fields and resources had to be defended. Chickataubut was often challenged by other tribes from the north and west seeking to take over this valuable territory.”

The Commission voted unanimously to consider the quarry as a Boston Landmark and directed that Bagley undertake further study for the formal designation process.

We asked Ed Quill, author of the recent comprehensive history of the tribe, When Last the Glorious Light: Lay of the Massachuset, about the quarry. “I didn’t know about Mattapan quarry, but that district played big role in early days of Colonial-Native intercourse,” he said. “I’m surprised there aren’t more of such recognized sites.” (Quill tells us “Massachuset” is the most faithful spelling of the tribe’s name.)

Bagley said he’s now doing a lot of work with the Massachusett Tribe of Ponkapoag, descendents of those who quarried there to finish a draft study on the quarry and send it to the Commission.

He said he needs to review the wording with the tribe regarding the characterization of the place. The site needs to be protected to allow traditional tribal activities but also, as with all landmarked properties, ensuring preservation. For example, how much public access will there be? The City of Boston Conservation Commission owns the land now, so Landmarks and the tribe and the Commission will work together to determine how to steward the site going forward.

Technically, Bagley said, it is an Urban Wild, preserved as undeveloped land. By spring or summer 2022, the parties will have worked out the guidelines. There will be some internal discussions among tribe members to arrive at their position.

“What we have discovered is a vast majority of the quarry has survived intact for thousands of years and represents a remarkable asset of Massachusetts native landscape preserved in Mattapan,” Bagley told Landmarks, according to the script he kindly provided for us.

“Here and nowhere else can one quarry this beautiful material. The place has an above-local significance because it was a unique stone material source traded over thousands of years as far away as Rhode Island. The Massachusett Mattapan Quarry deserves a place on the list of Boston’s most significant cultural and historical places as a Boston Landmark.”

The stone is unique, as Bagley related it, formed more than 600 million years ago. The area was part of a volcanic chain of islands called Avalonia, below the equator. A couple of hundred million years later, those islands butted into early North America and formed both part of New England and Northern Europe. The Blue Hills, the Lynn Hills and the Mattapan Hills are part of that history.

The Rhyolite stone was valuable for making tools.

“Members of the Massachusett Tribe set up a village along Mattapan/Dorchester and Milton and called it Neponset – also the name of the neighboring river,” the Dorchester Reporter article said. “In doing so, they purposefully sought out the Mattapan Rhyolite Quarry for toolmaking materials and there still remains great evidence of their ancient work on the site even today – as it unbelievably has remained relatively undisturbed since at least the 1930s, if not longer.”

The site is also known today as the Babson-Cookson Tract.

Bagley told the Commission that the indigenous communities of North America sought out rhyolite and other silica-rich and fine-grained stone materials as outcrops of bedrock. “Though no archaeological survey has occurred in this location, other Massachusett quarries where there has been survey in the 1980s and 1990s have shown that there is an extremely high quantity and percentage of shattered stone piled up from the initial quarry working of the larger stone into smaller more-manageable sizes, with workshops to refine the stone into finished tools done nearby or at other sites,” he said.

Archaeologists, who have long called this material Mattapan Banded Rhyolite, “have cataloged the Mattapan stone on Native sites in four Massachusetts counties including the towns of Bellingham, Bridgewater, Canton, Carver, Framingham, Freetown, Lakeville, Marshfield, Norfolk, Oak Bluffs, Quincy, Wakefield, and Watertown,” Bagley said. “Beyond Massachusetts, Mattapan rhyolite has been found at a Native site in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.”

“This quarry was active before the construction of Stonehenge or the Pyramids of Egypt,” he added,

The quarry was used again in the 20th century, Bagley said. A William Barry sold crushed gravel to the City at $1.23 a ton, records show. But was it Mattapan Banded Rhyolite that Barry sold – or was it Sally Rock Rhyolite from Crane Ledge quarry in Hyde Park, which Barry also owned?

Maybe further research will find out.