15 Nov 2019 People In Preservation: Boston Parks Department’s Kelly Thomas

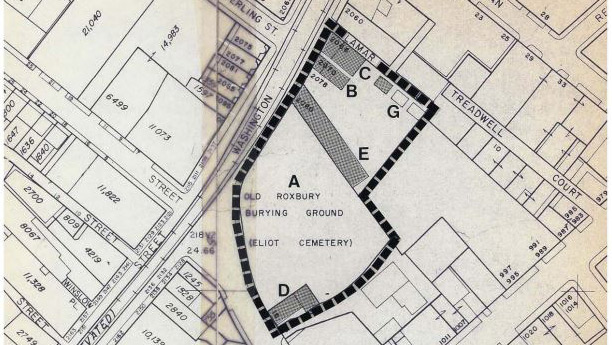

Wedged between Washington and Eustis Street, the Eliot Burying Ground one of Boston’s oldest burial sites. The historic grave site is part of a larger collection of landmarks in the area known as The Eustis Architectural Conservation District. The district is comprised of the Eliot Burying Ground, the structures at 2066, 2070 and 2080 Washington Street (The Nawn Factory), and the oldest remaining firehouse in Roxbury at 20 Eustis Street (HBI’s headquarters).

As one of the city’s oldest historic landmarks, the Eliot Burying Ground has withstood centuries of New England winters and many of the slate, brownstone, and marble stones require care and conservation. Since moving in HBI has witnessed upgrades to the site including, restoration of the iron fence, new interpretive signage, and the addition of paved pathways to allow easy access to all corners of the site.

HBI has volunteered to work with Kelly Thomas, Director of Boston’s Historic Burying Grounds, of the Boston Parks Department to inventory and assess all of the gravemarkers in the Eliot Buriying Ground, and set a course for their preservation. Kelly has worked in Parks Department since 2000 as a program manager and director of the Historic Burial Grounds office.

We spoke with Kelly to learn more about her work:

What has kept you in your position for two decades?

Kelly: I find the work truly interesting. Just when I think I know everything about these sites, I start doing research for a newsletter article, and I discover something new. Most of the time, I am surprised by how many people are actually buried at the site. For example, for Bennington Cemetery in East Boston and The South End Burial Ground, both look empty and South End only has about ten stones. Upon further research, I discovered that it was closed to new burials in 1906 (if you hadn’t already purchased a plot, you couldn’t be buried there).You look at it and you have no idea that there are an awful lot of people buried without gravestones. Many people think every person had a headstone, but they don’t. Maybe it was monetary, or not a social practice for everyone.”

What is fieldwork like? Do you have a favorite site?

Kelly: I am on-site often. It’s always nice to work in the sites on the nice days, but sometimes you have to work out in all weather, especially if there’s a problem or there’s a project in progress that can’t wait. I come prepared. I have boots for every weather and jackets with me to be ready for anything.

I would say that Dorchester North is my favorite because it has records that span five centuries. It is a special case, because normally we don’t allow people to be buried there, but in the early 2000s, we laid a woman’s ashes to be with her husband’s, which was a pretty rare case, but we felt like it would be cruel not to. It’s also the site that is closest to my house, so it’s the one I know best.

What makes up the biggest part of your job?

I think of my work as preservation from the sense that I care for the welfare of the whole of burying grounds. That is also what I studied in school. I also oversee the conservation, the more detailed and technical aspects for the stones and the elements of the grounds. Restoration projects take up most of my time, and those include design and construction. I hire people like a landscape architects and they plan the construction documents, depth for excavation, pruning, and other little caretaking details. We put all of our projects out for bid and oversee the work.

What has you most excited about your work for the Eliot Burial Ground?

I have done a lot of work in Eliot and that site really feels old to me, maybe it’s the small size of it. There are a lot of members from first church of Roxbury in the 1630s, and the church kept really good records. There are diaries and they have death lists and commentary about the members burials. Those stories have stuck in my mind because it is information that I didn’t have for other sites.

That site has the oldest existing grave marker, for Samuel Danforth, in Boston — it’s the earliest one that has surviving or the earliest one. The site’s antiquity is what speaks with me the most. There is also a special headstone on the grounds; it’s a series of four connected headstones with a skull at the top. The stone remembers four children who died over four years and their mother who passed a year after them all.

Is there a project that you are really proud of?

Kelly: The project at the Granary Burying Ground was one of more logistically challenging projects to date. The work included widening the front pathways, put in new pathways; we reconfigured the pathway at the Hancock monument. The original walkways were super narrow, and could only accommodate two people wide. The people who went off the path were compacting soil and erosion. The location is tricky, there was archaeology and pruning to get light in for the grass.”

—-

HBI is grateful to Kelly for here years of work preserving Boston’s historic burying grounds! Our work with Kelly in HBI’s backyard will continue through to the spring as we make our way through inventory and later conservation plans for the broken stones. Stay tuned for more discoveries and photos of stones from the burial ground.