February 28, 2021 Restoring the Stained Glass at Roxbury’s St. Luke’s Chapel

St. Luke’s chapel was designed by Ralph Adams Cram, a famed architect who popularized the modern Gothic revival. Under the direction of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts, HBI has worked as consultants to Spencer, Sullivan, & Vogt to document the existing conditions and create options for preservation and rehabilitation, including the potential for shared space with other church-sponsored programming and compatible community organizations. Read below to learn more about the marvelous and mysterious stained glass windows written by Curtis Perrin.

Byron Rushing has sometimes mentioned an idea he has for a stained-glass tour of Roxbury because of the number of important examples of the glazier’s art across the neighborhood. These are seen by individual congregations each Sunday, and it would be nice to bring other people to see these windows because they have such presence and tell so many stories.

While the abundance of fine glass abroad in great cathedrals needs no introduction, the less familiar wealth of windows in Roxbury churches includes a range of notable works by Tiffany, LaFarge, Connick, MacDonald, and many other great names in this art. These Roxbury windows are not always in their original positions, moved sometimes when buildings have been sold or damaged. For example, three Roxbury LaFarge windows are now a dramatic greeting to visitors right inside the front door of the Boston College Museum of Art. Yet there are so many still intact in Roxbury that it would be a full tour indeed. It would be augmented by at least one more because one Roxbury window will soon be returning from a short time away.

This home-coming window is the one from St. Luke’s Chapel that because of its condition had to be removed last year to secure it from risk of damage while money was being sought to restore it. SSV brought in stained-glass expert Roberto Serpentino, a frequent collaborator with us, to do this delicate removal work, and it has been carefully crated and stored in his studio awaiting the moment that has now arrived, which is that there is new grant money to cover its restoration.

This money comes from an application to the Henderson Foundation that SSV made last fall on behalf of the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts. Grant money in this fund comes from a fortune left to the people of Boston for enhancing and beautifying the city, and the Fund’s designators have now made a generous award of $40,000 to restore the principal window at St. Luke’s as well as smaller repairs on the other windows and the gothic window frames. With this award, the long and meticulous process of restoring the window will begin. Once complete, the grant money will allow the window again to rise up and be an example of something to look at, and look through. This window, like all the windows in Roxbury, shapes a gaze onto many stories.

Some of these stories start on a very small scale. Each stained-glass window is an assembly made of many fragments, held together in a delicate hanging web of lead to create a sum that is more than its parts. The individual pieces of glass often have stories in their own right, and some even have their own specialized names – some legendary within the trade. Via processes their creators often kept secret to the grave, each color and texture of glass is the result of a chemistry and artistry of rare compounds, minerals, and skill. We can wonder about what effort went into producing these and think about how even in the Middle Ages great efforts and cost went into obtaining these elements from far away sources. Each piece has its story in this sense, and the quest to replace broken ones is often quite a complex matter of recycling salvaged fragments from elsewhere or with luck recreating the technique by which it was first made.

There is as well the story of the artistic composition of any given window. Many windows, especially in more modern times, are attributed to specific artists. There were artists who were master glass makers, and also artists in other media like painting, who sometimes tried their hands at stained glass – like the stunning examples by the American impressionist painter Robert Reid at the Unitarian Memorial Church (also an SSV client) in Fairhaven, Massachusetts. Fairhaven is home to one of the world’s greatest displays of stained glass, yet it is the only time this painter worked in it, so it forms a resounding beginning and ending of a glass career. This is but one of many such tales of artistry, ambition, achievement, and sometimes rivalry.

Just as often, or perhaps more often, stained glass windows were not attributed to makers. This anonymity may link back to early Christian ideas that it was the job of art to glorify divinity, not call attention to artists. Though selflessness may be the reason we do not know the makers of many stained-glass windows, it can just as often be that records were incomplete. The window at St. Luke’s falls into this category, although Roberto Serpentino has conjectured based on the style that the artist could be either Frederic Crowninshield or George Hawley Hallowell. Following these leads, SSV’s research uncovered that Ralph Adams Cram, the chapel’s architect, had a close relationship with Hallowell and even funded his study tour of Italy around 1900 and called him “a genius,” lending weight to the theory that Hallowell designed this window due to his close connection with and admiration from Cram.

Recently, we were very happy to receive independent suggestions Hallowell might be the right candidate when Lance Kasparian, himself a stained-glass expert, shared a theory that he too thinks this window is Hallowell’s work, possibly his first window. Hallowell was like some of the artists mentioned above in that he did not do much work in stained glass and is principally remembered for his paintings of the Maine coast. While our theories are tempting, nevertheless Cram did write in his 1937 memoir that Hallowell “had done nothing whatever in the line of religious art” prior to his 1903 altarpiece at Cram’s All Saints’ Ashmont. St. Luke’s dates to 1901, which may complicate things, or the window could have been installed later. As Kasparian pointed out in his remarks, Hallowell remains somewhat an enigma because he died young. This brief career may explain some of the atmosphere around Hallowell that is so much like the mists of Maine he painted. For now, we will have to choose our stories about this artistic work’s origin carefully.

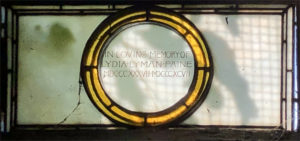

While we do not have the full story of its creator, we know a lot more about who probably paid for St. Luke’s window because it contains a dedicatory script to Lydia Lyman Paine:

IN LOVING MEMORY OF LYDIA LYMAN PAINE MDCCCXXXVII – MDCCCXCVII

THIS IS THE VICTORY THAT OVERCOMETH THE WORLD EVEN OUR FAITH

Both Lydia Lyman Paine and her husband Robert Treat Paine are recalled around Boston for the legacy of their philanthropy, and this window forms part of that story too. In fact, the circle around St. Luke’s at the time it was built included illustrious figures like Phillips Brooks and bishops of the Episcopal Church. Perhaps some of the financing for Cram’s gemlike design fitted out with such quality artwork came from sources like them – certainly, the money for the window did. It could have been a gift arranged by Paine’s husband (he lived till 1910), or via one of their children, who had active ties to the Episcopal Diocese of Massachusetts.

What the window depicts is also interesting because it seems obvious at first until you think about it. We see two angels, a red and a blue one. But why are they here? Why aren’t they named? Are we able to identify one by the attribute of carrying a basket of fruit? One guess offered is that the fruits represent gifts of the spirit being brought to us. Yet just as quickly another theory arises that the fruits are a harvest of souls being taken to heaven. Whether things are coming or going, it is certainly a beautiful set of images, and a somewhat uncommon arrangement with bright spots of color set amid larger areas of clarity, and with the Holy Ghost – third part of the trinity and of this composition in glass – represented in the form of the descending dove superposed against a star and golden cross in the central quatrefoil. Yet the speculations above show things are not always clear, especially to a close scrutiny. In the work on the restoration, we hope further attention will reveal more of what for now remains potential.

The second line of the inscription comes from 1 John 4:5 (KJV) and could allude to a theme of eternal life, which is potential indeed. Starting from this point, one could make a story just as easily as find one in the decision to commit oneself to something of such infinite scope. And we do find there has been a story of many commitments coming together – across time – around this window. It has been the occasion for the memorialization of a person, and it serves as an object lesion in certain techniques of art and the lives of artists. It has been the impetus to receive grant funding to beautify the city. Even beyond all that, it has brought many people together, historically, and today – and hopefully for the future too. It has been one condition for assembling a committee of architects, planners, restorers, church leaders, neighborhood residents, and most importantly the St. John’s and St. James Church congregation, who have shepherded this window ever since 1968, when they came into being out of the merger of two Black congregations, and they have been here ever since.

I asked Cabral Walters from the congregation what stories the window prompts for him. He reflected on how seeing figures of Marcus Garvey and Frederick Douglass in the stained glass at St. Cyprian’s, not far from St. Luke’s, was an invitation to him from a work of stained-glass itself to observe it at its fullest. From that moment, he saw what stained glass can do. “You are looking at an image, but it’s not just an image. It’s like how a person could spend years worshiping at church in a way that’s doing the motions, and after a time you start questioning things and wondering why they are there.”

That is when the image in the glass is something we look at in order to look through, when it makes an impact. Such things will reveal more for those having that stance to look with questions.