07 Mar 2023 Rooting Out the History of Your Home: Your DIY guide to research

Historian and preservationist Sally Zimmerman prepared this step-by-step guide to researching the history of your house. Boston is rich in on-line and archival resources that are accessible to the public. Follow Sally’s expert direction to discover who built your house, or lived in it over time.

If you live anywhere other than a brand new building, you probably only know the immediate history of your home, namely, who you purchased or rented it from. But perhaps if you are looking around your neighborhood and wondering why it looks the way it does, or thinking about making some changes to the building you own, you may be curious to find out more about its past.

Your first questions are probably “how old is my house” and “who built it”? When you’re out in your neighborhood, you might notice the houses on your street are all quite similar, or very different, from each other, or include a mix of stores and houses, and ask “why?”. After that, however, I hope you will ask yourself, who lived here before me? What kind of work did they do? Who lived with them, or nearby?

To me, these are important questions because the answers challenge us to remember that we are just the most recent participants in the ongoing history of the places we call home. The people who shaped our neighborhoods and community were real people like us, with hopes, dreams, and aspirations for their lives, some of the best reminders of which are the buildings and landscapes they created, used, and left for us to use. They are the ones whose roots give us a tangible sense of the history we share in our homes. As a preservationist, I hope that by digging around in the history of your home and neighborhood, the roots you uncover will enrich your understanding of the past and inspire you to preserve your piece of it.

Scratching the Surface: MACRIS

The quickest way to research your home’s history is to use the Massachusetts Cultural Resource Inventory System, or “MACRIS”, an online listing housed at the Massachusetts Historical Commission which is mandated to document cultural resources (i.e., buildings, sites, landscapes, districts, and objects of historical importance) throughout the Commonwealth. Included on MACRIS are all the historically/culturally important properties in Boston that have thus far been documented by the Boston Landmarks Commission (BLC) and its consultants over the last 40+ years.

In Boston, while a vast amount of important property research has been completed, much of the documentation contained in MACRIS reflects traditional concepts of what has been considered “historic”: this means that many, if not most, individual buildings have not been separately or fully documented. Preservation advocates are working to expand the information collected and recorded in the MACRIS database to include the history of the 20th century and of the city’s BIPOC residents. But even as a partial, imperfect, or potentially biased record, MACRIS provides the best starting place for historical property research.

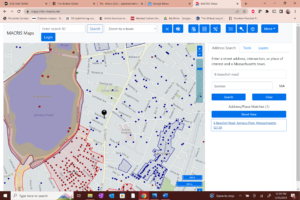

Within the MACRIS database, the MACRIS Maps feature allows you to quickly focus in on properties in Boston by narrowing the search to your specific street address. Searching MACRIS Maps by street address, for example, brings up a map of everything that MACRIS has already captured about the area around your street address. Your location will be marked with a black pin if there is no individual information on the property, or with a blue, red, or green dot or square if there is further information available.

Figure 1: A screenshot of the MACRIS Maps location for 6 Beaufort Road, Boston shows a black pin at the location with a blue dot nearby (above). The blue dot shows that the BLC has completed an inventory form for property on Lakeville Road, which is part of a 1905-1909 apartment complex encompassing the whole block between Beaufort and Lakeville roads. Blue and red dots and shading nearby on the map indicate localities with further documentation in the MACRIS files.

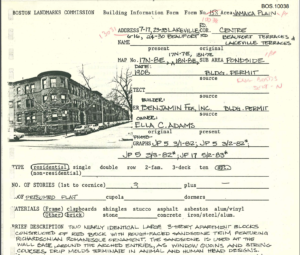

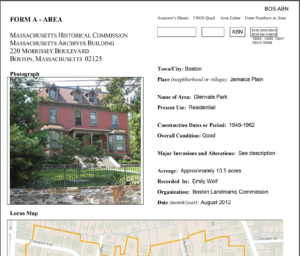

Clicking through on the colored dots and squares allows you to download a digital scan of a paper survey form (also called an “inventory form”) with the historical research already completed for that property. Clicking on outlined shaded areas in the surrounding locations allows you to download larger, multipage “Area” inventory forms where blocks of properties have been documented.

Figure 2: A screenshot from MACRIS of the original 1983 paper inventory form for the complex at Lakeville and Beaufort roads, completed by the BLC and scanned into MACRIS. It shows the original owner was Ella C. Adams and the architect was Benjamin Fox, with a building permit date of 1908.

Figure 3: A screenshot of the 20-page Area inventory form for the Glenvale Park area of Jamaica Plain, shown in Figure 1 as a blue shaded area (labeled BOS.ARN) at the lower right corner of the MACRIS Map. The Area forms contain information about neighborhood development and calls out notable buildings and features in the Area.

Like all digital databases, MACRIS takes some getting used to, but by starting from MACRIS Maps and your street address, scrolling around in your neighborhood, and then clicking through to download information on the areas marked with shading or colored dots, a great deal of historical data on the location can be gleaned, and the outline of your neighborhood’s historical “roots” will begin to emerge.

Digging Deeper: More Detail and a Fuller Picture

In your explorations of the MACRIS database, you will have picked up the main threads and background of the history of your property and its surroundings. MACRIS Area forms often provide names, such as the original property owners active in your area and perhaps some architects or builders associated with its more prominent buildings or landscape features, along with construction dates for those buildings and features, and a brief narrative on the architectural and historical development of the area or neighborhood.

But if you want to know more, or if you haven’t located much information on your property through MACRIS, you can turn to other historical sources and online data to get a better picture of the history of your home and its surroundings.

For easily accessed, accurate, and visually compelling information on individual properties and their surrounding development, nothing can top the historical maps of the 19th and 20th centuries, especially the large-scale maps known as fire insurance or real estate atlases.

The insurance atlases are beautifully drawn, very colorful bound sets of maps of cities and towns capturing in detail a historical moment in their development. They are an especially rich source of information for the City of Boston. Given Boston’s size and prominence in the 19th and 20th centuries, the city changed dramatically in short spans of time. The insurance atlases provide a vivid picture of the changing patterns of Boston’s development, street by street and block by block.

The atlases, which documented all major cities and many smaller cities and towns nationally, began to be published in the 1870s. They were originally compiled to allow insurance companies across the country to write policies on properties they might never be able to inspect directly on site. The atlases were then carefully updated every 20 years or so illustrate the changing development of each location. They stopped being updated around 1940 as newer ways of documenting construction and infrastructure became available.

Each “plate” (or page) of an insurance atlas is a snapshot of the changes any given block experienced. The maps show bodies of water, streets, local infrastructure (like rail and gas lines, utility poles and streetcar service) but also the footprints of buildings, their property lines and lot square footage, their owners’ names, and much more. Brick buildings, for example, are shown in pink, frame structures in yellow, and outbuildings appear with an “X” in the outline of the footprint. Driveways and paths show up as dotted lines heading from the street to the front door or the stable.

In Boston, the best local source for the full range of published insurance atlases is the Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center at the Boston Public Library. Housed in the main branch in Copley Square, the Leventhal Center is a major cartographic archive, holding a vast digitized catalog of rare maps from around world and spanning centuries of mapmaking.

Fortunately for local history explorers, the Leventhal Center has a full catalog of Boston’s fire insurance atlases and its newly-debuted digital “Atlascope” feature can perform magical feats in helping you find the needle that is your property within the haystack of the many different atlases published for the city. Using the locational software in your computer, “Atlascope” will take you directly to a “porthole” detail of the earliest published atlas map for your location. The “porthole” nests into a modern day base map of your section of the city. A drop-down menu links you to all the subsequent insurance maps for that location, while scrolling allows you to extend the historical viewing area out into the larger neighborhood. Using those features, you can travel back and forth in time around your neighborhood to see how it has evolved from the mid-1800s to the present.

Figure 4: The Atlascope image for Lakeville Avenue, Jamaica Plain, from the Leventhal Collection; Hopkins, G.M. Jr., Atlas of the County of Suffolk: West Roxbury, Vol. 5 (Philadelphia: G.M. Hopkins & Co., 1874) shows the property with the house and stable of T. W. Seaverns on it. Just north are two houses and a stable owned by Chas. H. Adams. The thick line in Centre Street is the horsecar line.

The Atlascope image for Lakeville Avenue (now Road) shows an earlier house on the site, owned by T. W. Seaverns. It also contains some additional information relevant to the apartment buildings that we first encountered in the MACRIS Maps search for Beaufort Road, shown in Figures 1 and 2. The name “Chas. H. Adams” on the next property north of the Seaverns house suggests a connection of that property with the construction of the Lakeville and Beaufort road apartment complex by Ella C. Adams in 1908. As will be shown below, there is, indeed, a connection.

The Leventhal Collection is ideal for properties in Boston, but to search for historical maps in other areas, a good source is HistoricMapWorks.com. An online retailer of images of historical maps, HistoricMapWorks.com is a reliable source for period maps throughout the country. It is also the best place to purchase a high-quality print of a historical map of your neighborhood. Original copies of the atlas plates are available from antique stores and booksellers, but these copies come from bound atlases that have been taken apart for sale. It’s far better, from an archival perspective, is to preserve these atlases intact and get yourself a nice, scanned copy to hang on your wall.

Hitting Pay Dirt – Who Lived In My House?

The insurance atlases bring the historical past of your neighborhood to life, but they also give you the names of owners of your home over time. With that information, you can begin tracking down the people who built or lived in your place and finding out more about who they were. Taking that next step involves accessing the types of information that historians call “primary sources.” A primary source is information that was created by people living at the time of its creation. It could be an obscure letter from a Civil War soldier or the diary of a colonial-era seamstress, but for local history research, there are other more easily accessed primary sources that can be consulted to find out more about people who lived long ago.

The two best sources to start with are 1) the population records of the U.S. Census, compiled once every decade from the 1790s to the present, and 2) what are called “city directories,” the old-time equivalent of the printed telephone directory. Because the information they contain is more limited, I’ll start with the city directories.

City directories listing residents and businesses were published frequently in Boston from 1789 into the 1920s; specialized business directories (used for commercial marketing purposes) were available into the 1970s, although by then, the telephone book and Yellow Pages had largely supplanted them. These directories usually listed residents and businesses both by name and by street address, and they included tenants, not just owners, as well as the residents’ occupations. If you have the name and a date for an owner from your Atlascope search, you can begin to learn more by locating them in a city directory. A Wikipedia site for “Boston Directory” lists all known city directories for the city with links to the repository in which the directories can be found.

The private archive of the Boston Athenaeum has the most complete set of these directories and has provided free online access to their collection of directories. By selecting “Browse Full Collection” on the home page of the Boston Directory page, the entire catalog of directories will be listed chronologically. Opening selected directories will allow you to search for names of owners you have identified for your property. Also listed with those owners will be any adult children living with them at the address, along with occupations for all adults at that address.

Figure 5: The 1858 title page of the Boston Directory from the BPL web page on city directories (https://s3.amazonaws.com/libapps/accounts/4901/images/BCD_1858.jpg)

Turning to the U.S. Census as a source for information about individual property owners, I have found that the most expeditious way of searching the vast archive of the census is via a paid subscription site for genealogical research, such as Ancestry.com. There are many free sources of genealogical information online, but I have found Ancestry.com, which offers a short-term free trial, to be the easiest to navigate. With subscription access to Ancestry.com, you can search on the individual by name, location, and rough dates, and an array of sources will be revealed, in addition to any family trees that have been publicly shared. Ancestry.com searches almost always include census and city directory listings, military service information, dates of entry and exit for foreign travel, a place of burial (via FindAGrave.com) and in some instances, will and probate records.

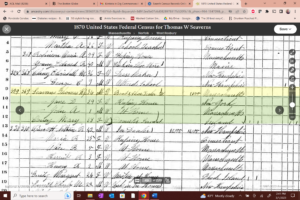

Information to be gleaned in the census records varies by the decade in which the census was conducted, with individual households starting to be named in the 1840 census and data becoming ever more detailed after that. For example, the 1870 U.S. census entry for Thomas W. Seaverns, the owner of the property shown in the 1874 atlas image in Figure 4 (above), includes his age, gender, race, occupation, place of birth, the value of his personal property, and his citizenship. All members of his household are cited, including his 38-year old Irish-born “domestic servant,” Mary Coney. Miss Coney’s census data shows both her parents were also born in Ireland and that she could not read or write.

Figure 6: A screen capture from Ancestry.com of the 1870 census entry for Thomas W. Seaverns, Jr., a 34 year old boot and shoe dealer, his wife Jane D. (age 29), their 1 year old son, John A. and servant, Mary Coney.

Once you have tied a property to a specific owner at a certain date (i.e., Thomas Seaverns on Lakeville Avenue in 1874), you can then track that owner backward and forward using the links Ancestry.com provides to additional sources. In that way, I was able to learn that Thomas Seaverns, the boot and shoe dealer, was the son of Thomas W. Seaverns, a grocer in downtown Boston who built the Lakeville Avenue house in 1842. Following Thomas Seaverns, Jr.’s death in 1903, the property was sold to Ella C. Adams and by 1905 (according to the G. W. Bromley atlas), Mrs. Adams had constructed the first of two brick apartment buildings on the site. By 1910, her son, Winthrop, was living in one of the recently built buildings on the old Seaverns house location.

Figure 7: A screen capture from Ancestry.com of the 1910 census entry for Lakeville Place (now Road) includes Winthrop Adams, age 28, a wholesale grocer, his wife of two years, Marion (28) and their servant, Mary McDonald (29) at #17. Further investigation confirmed that Winslow Adams was the youngest of Charles H. and Ella C. Adams’s four children, that he grew up in the house shown in Figure 4. and was renting an apartment in the complex recently built by his mother.

We’ve seen how, starting with the basic information provided in the MACRIS database from the thousands of inventory forms that are already well researched and available online, a more complete picture of specific properties can be filled in using additional historical sources, such as historic insurance atlas maps that are also fully accessible for free online. Finally, by supplementing that information with research in huge public databases, such as the U.S. Census records, either through paid services such as Ancestry.com or other family search sites, the people and lives behind the words and images begin to come into focus.

There’s no reason to stop there, as many other public data sources can be checked for further information once you have some basic facts about the age, owners, and background of your house. Classically, people talk about tracing the deeds to their property, but accurately tracing deeds requires very close attention to property boundary descriptions, and you might not need that information if you’re already familiar with the historical development of your neighborhood.

You can fill in more information about your house from other historical sources such as the Suffolk County probate records, City of Boston building department files, and the extensive photographic archives at the Boston Public Library, the Bostonian Society and the smaller local historical societies that exist for most of the Boston neighborhoods that were once independent cities and towns (Brighton, Dorchester, Jamaica Plain and others).

Having dug through some of the topsoil around the roots of your home’s history, you’ll be able to dig deeper as your interests and curiosity allow, but you will have a better sense of how the past has shaped the character of your house and neighborhood. And perhaps, along the way, you’ll have found a deepened interest in your own home, a better awareness of your place in its life, and a commitment to caring for it so that its story can continue to enrich and inform those who come after us.