01 May Roxbury: Back to the future of Economic Re-development – Part 3

This is Part 3 in the series of blogs whereby HBI’s Jeff Morgan synthesizes the history of Roxbury Neck to help inform the direction in which new Roxbury developments may shape the future of the neighborhood. Check out Part 1 – Early Roxbury before the Revolutionary War and Part 2 – The Impact of the Revolutionary War on the Industrialization of Roxbury

From the Industrialization to the Urbanization of Roxbury

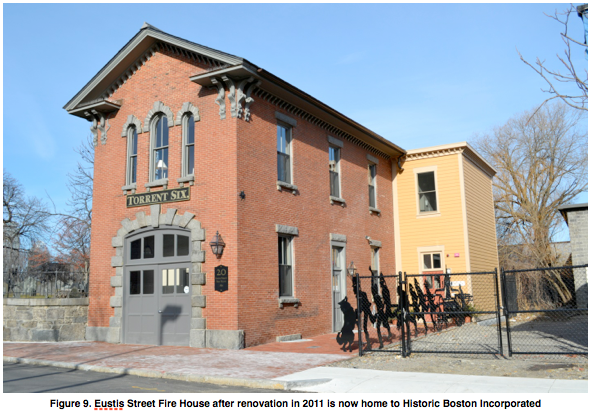

On March 26, 1846 Roxbury became a city and as a result, many public improvements occurred such as the widening of Washington Street in 1855 along with the construction of a firehouse and other buildings to support the industrialization and modernization of Roxbury.

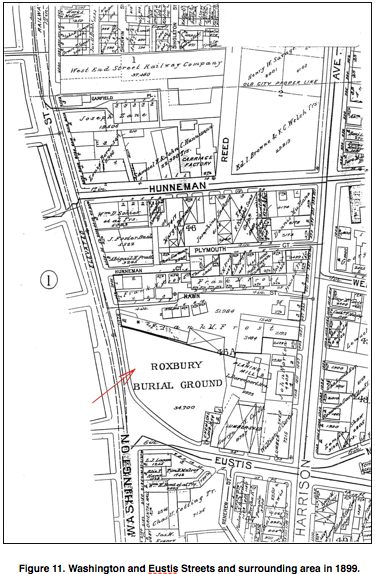

Built in 1880, the Owen Nawn Factory building (Figure 10) represents the completion of the transition of this section of Roxbury from a rural to an industrial area. Located at 2080 Washington Street at the northeastern edge of the Burying Ground (Figure 1 in Blog Post 1 and Figure 11), it is a modest two-story vernacular Italianate style factory building. It was named for its owner, Owen Nawn, an Irish immigrant and Roxbury building contractor and developer. The simple cornice line, flat roof and simple segmental arched window and door surrounds lend the building a utilitarian simplicity appropriate to its commercial function. The cobblestone court which links the factory and the Cunningham and Doggett Houses (Figures 5 and 6 of Blog Post 2) was once a well used and busy place. Tenements occupied the site near the rear portion of the factory building. Josiah Cunningham’s candle-making shop and barn also fronted on the court. Maps indicate that the cobblestone passageway extended through to Harrison Avenue in the latter part of the nineteenth century and was known as Nawn Street due to the large number of buildings lining the street owned by Mr. Owen Nawn.

Built in 1880, the Owen Nawn Factory building (Figure 10) represents the completion of the transition of this section of Roxbury from a rural to an industrial area. Located at 2080 Washington Street at the northeastern edge of the Burying Ground (Figure 1 in Blog Post 1 and Figure 11), it is a modest two-story vernacular Italianate style factory building. It was named for its owner, Owen Nawn, an Irish immigrant and Roxbury building contractor and developer. The simple cornice line, flat roof and simple segmental arched window and door surrounds lend the building a utilitarian simplicity appropriate to its commercial function. The cobblestone court which links the factory and the Cunningham and Doggett Houses (Figures 5 and 6 of Blog Post 2) was once a well used and busy place. Tenements occupied the site near the rear portion of the factory building. Josiah Cunningham’s candle-making shop and barn also fronted on the court. Maps indicate that the cobblestone passageway extended through to Harrison Avenue in the latter part of the nineteenth century and was known as Nawn Street due to the large number of buildings lining the street owned by Mr. Owen Nawn.

During the late 1860’s Mr. Nawn acquired a number of properties in the area, including the factory site. He also bought land and constructed many houses in Roxbury and Jamaica Plain during the last quarter of the 19th century, thus contributing to the creation of what have been called “the streetcar suburbs.” He was also responsible for building much of the Metropolitan Railway and some of the elevated transit line and related structures at Dudley Station in 1901.

During the late 1860’s Mr. Nawn acquired a number of properties in the area, including the factory site. He also bought land and constructed many houses in Roxbury and Jamaica Plain during the last quarter of the 19th century, thus contributing to the creation of what have been called “the streetcar suburbs.” He was also responsible for building much of the Metropolitan Railway and some of the elevated transit line and related structures at Dudley Station in 1901.

In the 1850s housing development throughout Boston increased, but just as rows of elegant brick buildings rose on the streets of the South End, large opulent mansions began to go up in the Back Bay and as the wealthier residents of downtown Boston slowly became surrounded by more and more commercial buildings, they mostly opted for the Back Bay. The burgeoning immigrant populations of Boston, specifically the Irish, began to move into the South End and the Catholic Church followed, first building the Church of the Immaculate Conception, then founding Boston College, and culminating in the construction of a new cathedral on Washington Street at Waltham Street in 1867. The Panic of 1873 speeded up the process of decline of the South End, as wealthier residents fled in search of better value, real estate prices dropped as they left, and poorer immigrant families filled the Victorian buildings.

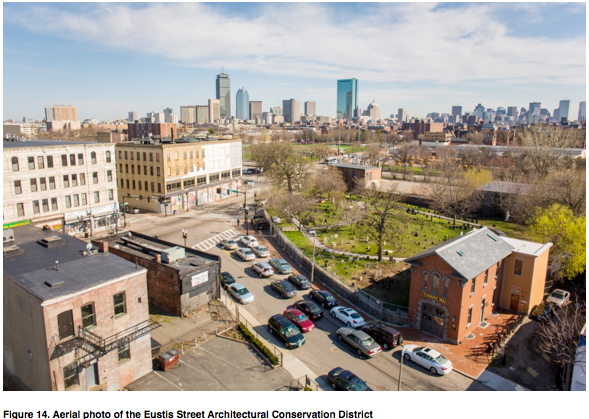

Each of the buildings and sites in the Eustis Street Area of Roxbury (see Figure 1 in Blog Post 1) has its own individual identity and speaks in a unique way to the development of Roxbury. Coincidently, the buildings and the burying ground they frame form a visually cohesive whole –a “distinct entity” in the Dudley Square area. There are also some interesting thematic connections between them, such as Jesse Doggett having been a fireman and being buried in the cemetery near his house. But it is as a collection of artifacts from the various periods of growth at the Roxbury Neck that the district is most significant. To be sure, this section of Roxbury was always a modest area, plagued by flooding and later by uncontrolled industrial growth. But the history is no less important than the history of more prosperous areas. And these historic resources, which tell an important story in Boston’s history, deserve the recognition usually afforded to more monumental structures.

Each of the buildings and sites in the Eustis Street Area of Roxbury (see Figure 1 in Blog Post 1) has its own individual identity and speaks in a unique way to the development of Roxbury. Coincidently, the buildings and the burying ground they frame form a visually cohesive whole –a “distinct entity” in the Dudley Square area. There are also some interesting thematic connections between them, such as Jesse Doggett having been a fireman and being buried in the cemetery near his house. But it is as a collection of artifacts from the various periods of growth at the Roxbury Neck that the district is most significant. To be sure, this section of Roxbury was always a modest area, plagued by flooding and later by uncontrolled industrial growth. But the history is no less important than the history of more prosperous areas. And these historic resources, which tell an important story in Boston’s history, deserve the recognition usually afforded to more monumental structures.

The South End and Roxbury seem to be coming full circle. The South End has once again become a desirable location to live with trendy restaurants and coffee shops, and Dudley Square is seeing significant investment with the redevelopment of the Ferdinand Building as part of the Bruce C. Bolling Municipal Building (Figure 12) and the new Tropical Foods grocery store (Figure 13). These recent development form the foundation of what is portended to be a renaissance of Dudley Square bringing needed services, housing and

employment opportunities to Roxbury.

So as Roxbury turns yet another corner of redevelopment and modernization to secure its future, let us, as a community, be mindful of how anticipated development in Dudley Square and the Eustis Street Architectural Conservation District (Figure 14) will relate to earlier development and honor the past while establishing a vision and setting a course for the future. Roxbury?s extraordinary history and its significant places are foundations for the cultural and economic development of all of Boston ? the stories of which are told through its historic buildings as remnants of a very rich past.