June 13, 2017 Seeing the Forest for the Trees: Preserving the Roxbury Legacies of Richard Bond and Henry Hampton

“A consideration of questions of community and conservation and how they relate to 88 Lambert Ave. in Roxbury, the house of early American architect Richard Bond and later of civil rights activist filmmaker Henry Hampton, which is being sold to a prospective developer. Curtis Maxwell Perrin works in architecture and is a Roxbury resident.”

My architectural mentors once said to me that buildings are like trees in a forest, a resource to use and conserve, and you should almost never demolish them because nearly any building can be reused. When one is in a forest, it seems reasonable to think that one would not ruin it by felling all the trees. However, right now in the “Boston forest,” logging is happening everywhere. We are in the midst of one of the greatest building booms the city has ever undergone, and the look of Boston will be forever changed by the decisions being taken these days. Much of this change is salutary, but it also seems to me that we have lost sight of the forest and are demolishing many buildings in a way that is wasteful.

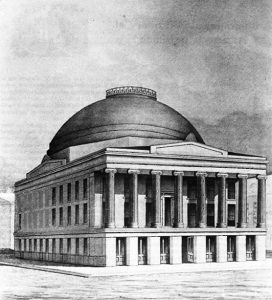

The now-lost Merchants? Exchange building in Portland, Maine

Demolition is the name of the game for many prospecting developers in my neighborhood of Roxbury, a place of great cultural and historical importance. In many (but not all) cases their goals are ruining our resources, which are not just buildings, but the networks of people that have formed in them over many years. Pricey new buildings are displacing people and wiping away the social stability of our neighborhood.

Many people are unaware that Roxbury is equally as old as the most venerated parts of Boston that nobody would dream of demolishing: the houses on Beacon Hill have their Roxbury equals too. Roxbury was a separate, rival town to Boston until the two municipalities merged in 1868. Before that, Roxbury was known for its elegant “country life” as a retreat from the busy life in the city of Boston, with large estates dotting the hillsides. Some clues of that world remain and should be preserved, not as shrines to the past but because they are keys to the continuity of many traditions and lives in the neighborhood, encompassing all generations.

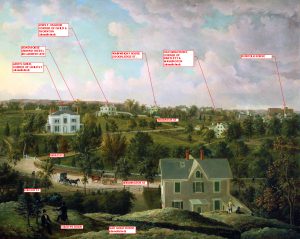

J.W.A. Scott painting

The J.W.A. Scott painting in the MFA preserves a view of this long-forgotten Roxbury from 1854, before the first building boom of the 1870s. While the scene may seem foreign (we are looking at the valley where the Bartlett MBTA Yard stood until recently along Washington Street), to the careful eye some remains of this period still exist. Many of the houses in the picture have been lost, demolished like trees cut down, but at least two of them remain. One of them, the Wainwright House, stands wrapped in aluminum siding and shorn of its wings at 2 Rockledge Street. Without maps and pictures like this, it might not be recognized for the important survivor it is; but there it is, still vital, still home to people, and still capable of reuse, and hopefully for a long time to come.

Another is the house at 88 Lambert Avenue, also in the painting, slightly obscured by trees. This was the home built for himself by Richard Bond, a prolific early American architect whose many commissions stretch from Massachusetts to Ohio. Among the many important churches and civic buildings Bond designed, best remembered surviving in Massachusetts are the First Parish Church in Cambridge and the Town House on the green in Concord. Bond’s most impressive project is the now-lost Merchants Exchange building that stood in Portland, Maine.

Bond was a taste-setter, and together with his partner Isaiah Rogers, forged an austere and monumental architecture that some people call the Boston Granite Style. Think of Quincy Market or the Bunker Hill Monument for surviving examples of this style by other architects. This was a style not limited just to granite, as is evidenced by projects both Rogers and Bond undertook using wood to imitate the smooth, quiet quality of stone.

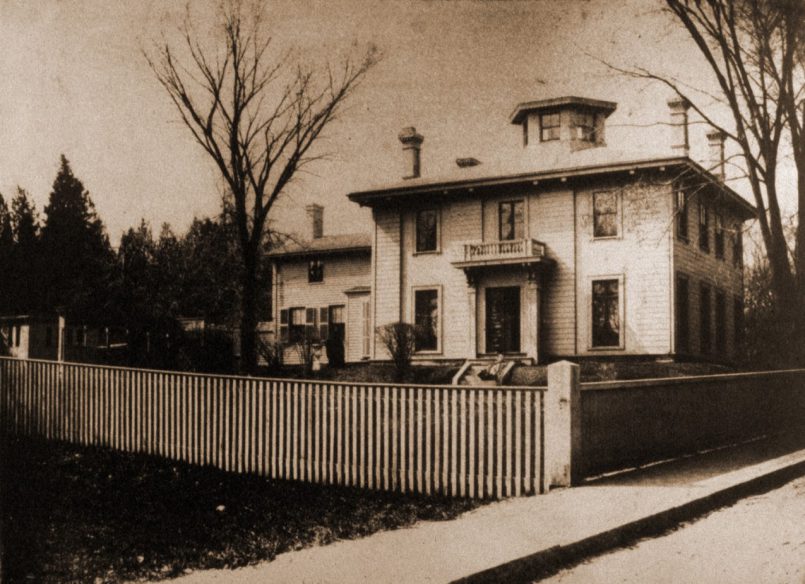

In its original appearance, Bond’s own house at 88 Lambert Avenue had a low hipped roof and four wide pilasters on the front giving it a Greek temple appearance. As was common back then, houses were often updated to reflect the latest tastes. In his lifetime, Bond later had Victorian Italianate elements added porches, brackets, cupolas, and corbelled chimneys.

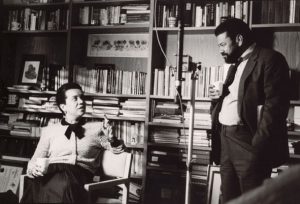

Henry Hampton (right)

Bond’s house has survived mostly intact including garden and outbuildings for 180 years, and it was also home to many other people whose story deserves to continue. That is, until recently, when the house hit the market and went under agreement with a developer. With extensive land, it seems a likely target for condos, which have been sprouting throughout our “forest of buildings” in ways that are so profitable to developers that they will often clear-cut history to make way for them.

But the Bond house calls out for a different fate. Not only was it a house that an important architect designed for himself, it also reflects the history made in Roxbury since then. In more recent times this was the home and studio of Emmy-winning African-American filmmaker Henry Hampton. Hampton’s studio Blackside produced over 65 civil rights documentary films that explored poverty, democracy, and diversity his best known work, among many, being the series Eyes on the Prize.

Thus, in addition to its connection to two important cultural figures, the story of this house represents a microcosm of Roxbury’s shifting history and the ways its legacy always has and hopefully always will accommodate new people and new types of use. This is an exceptional place worthy of conservation: many of these buildings can be reused and adapted to current needs without demolishing them, as the Alvah Kittredge house project undertaken by HBI not long ago shows.

The Bond House in 1874

The fate of houses like the Bond House, or nearly any house in Roxbury, is uncertain today given the development pressures, but these pressures have also ignited the urgency for action. There are a few tools available such as landmarking, conservation districts, and the like that can help in exceptional cases. But for the majority of buildings, like trees in a forest, what is needed is a sense of appreciation, which leads to an attitude of conservation and a mindset that will seek continued enjoyment of what we have that is already good and capable of reuse. One would not enter the forest to appreciate it and then proceed to cut it down. Just the same with our houses in Roxbury.