21 Dec The Atlantic City Boardwalk Decision: What Does It Mean for the Federal Historic Tax Credit?

A recent court decision on investor risk for the Atlantic City Boardwalk Hall has called the investment structures of the Federal Historic Tax Credits. Matt Welch describes the problem and potential implications for preservation projects and the credits in part three of our series on State and Federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credits.

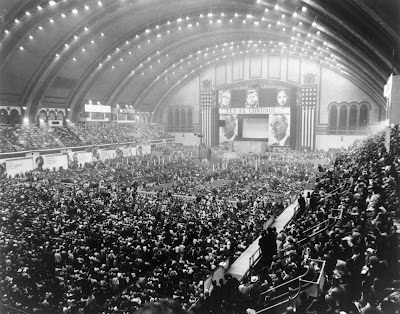

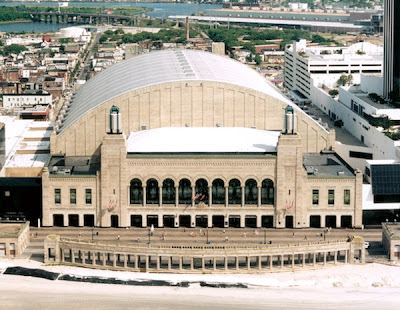

A recent court decision on investor risk for the Atlantic City Boardwalk Hall has called the investment structures of the Federal Historic Tax Credits. Matt Welch describes the problem and potential implications for preservation projects and the credits in part three of our series on State and Federal Historic Rehabilitation Tax Credits.After a corporation invested in the rehabilitation of the historic Atlantic City Boardwalk Hall in New Jersey in 2000, the IRS disallowed the historic tax credit that the developer passed through to the corporate investor. The IRS?s primary argument was that the investor lacked a significant assumption of risk (or reward) in the project, which, the IRS argued, meant that the corporate investor was not a genuine partner in the project for tax purposes. Ultimately, a tax court ruled in favor of the investor; on appeal earlier this year, however, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals reversed the district tax court?s decision, ruling in favor of the IRS. Indeed, the Court of Appeals agreed that the investor lacked any meaningful stake in the project: the payment to the investor was guaranteed, the investor did not contribute any capital until the developer actually secured the tax credits, and the investor reaped no benefits from any return on the project aside from its guaranteed distribution. The Court?s decision seems to underscore the notion that the IRS expects a corporate investor to join a developer in a rehabilitation project as a legitimate partner, albeit one that may incidentally receive a disproportionate share of the tax benefits resulting from the project, rather than joining the project as a nominal partner that is indirectly purchasing tax credits. In other words, Boardwalk suggests that the partnership between the developer and investor should demonstrate a business purpose (i.e. profit motive) for the investor.

In many ways, the Boardwalk decision creates more questions than it answers. For example, must a partnership between a non-profit developer of historic properties, which often undertakes projects that do not necessarily offer a significant upside, and a corporate investor be based primarily on profit motive? Furthermore, how much risk and reward must an investor assume to satisfy the IRS?s partnership ?eye test?? In Boardwalk, the decision did not hinge on the fact that there was too little risk, but rather that there was virtually no risk, as the investment was engineered for success. As a result, the Court evaded the question of exactly how much risk (and reward) an investor must assume. Fortunately for developers, some language in the decision did, however, indicate that the IRS is less concerned with the economic substance of a project partnership than whether that partnership furthers the Congressional intent behind the historic tax credit?presumably the rehabilitation of the nation?s historic properties.

Boardwalk?s impact on the historic tax credit market remains unclear, but the industry has certainly taken notice. Law firms are reconsidering the ways in which they counsel their investor and developer clients in structuring historic tax credit transactions to avoid the fate suffered by the investor in the Boardwalkcase. Strategies include allocating more risk and reward to investors, accelerating the date at which investors contribute to the project, and limiting the number of guarantees an investor requires of a developer. Nonetheless, developers are eager for the IRS to clarify its expectations, as the historic tax credit is often vital to the rehabilitation and preservation of historic properties.