August 20, 2012 The Bank Block in Hyde Park’s Logan Square

This summer, HBI was lucky enough to enlist the assistance of Haley Wilcox, a Boston University Preservation grad student, to intern with us. Among other helpful tasks, Haley spent part of the summer compiling a commercial case book of Cleary and Logan Squares in Boston’s Hyde Park neighborhood. She agreed to share some of what she learned about historic neighborhood centers here in her guest blog post. Enjoy!

In his provocative book How Buildings Learn, Stewart Brand describes commercial buildings as ?forever metamorphic,? changing constantly as a result of intense pressure to perform. He argues that a building?s ability to adapt to changing needs can determine whether or not a business housed in it grows or fails.

In Hyde Park, the Burnes Building housed a neighborhood department store for several decades, and took on many forms. As such neighborhood stores declined in favor of more suburban shopping, new uses were found for the buildings. In this case, large plate glass display windows were no longer needed on two floors, once the building was converted to offices and then other uses. In some ways, the building was adapting to the changing needs of the business, and in others, it was adapting to stylistic trends in the built environment. Nonetheless, despite its numerous changes, the core of the building is still recognizable.

As an intern in HBI?s Historic Neighborhood Centers program this summer, I have had the opportunity to dig into the history of Hyde Park, discovering its roots, and seeing how the commercial district in Cleary and Logan Squares has changed over time. In many ways, Brand?s book illustrates how Hyde Park?s built environment has responded to the needs or tastes of its people. One fascinating example is the Bank Block in Logan Square.

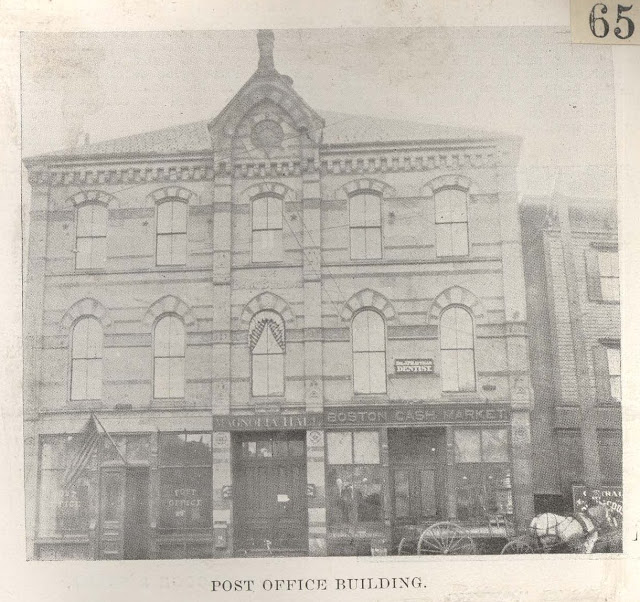

Built in the 1870s at the height of the Gothic Revival movement, which was led by prolific figures such as John Ruskin and William Morris, the Bank Block featured arched windows, multicolored patterned brick and stone masonry on the fa?ade, an ornately decorated central projecting bay, and a steeply pitched roof. Like Old South Church in Copley Square, completed in 1873, and Harvard?s Memorial Hall, which opened in 1877, the Bank Block stood as a testament to Ruskin?s ideas. An ardent advocate for the Gothic Revival, Ruskin believed it was this style that embodied moral truths, was reverent to nature and natural forms, and, most importantly, was a tangible expression of a worker?s (or in this case, a builder?s or craftsman?s) relationship to God.

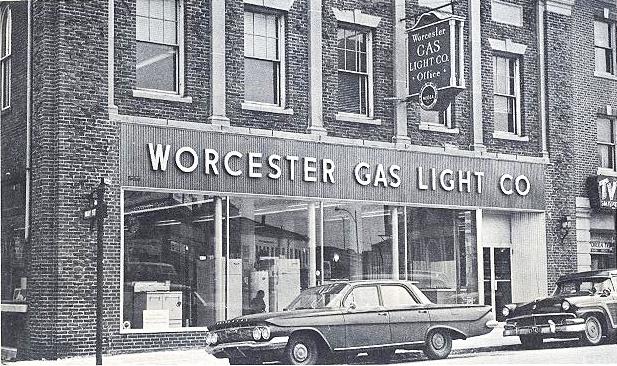

Looking at the Bank Block today, nearly all the evidence pointing to its Ruskinian Gothic beginnings are gone. The building underwent a significant alteration in the 1920s to its current Classical Revival form (which in itself is ironic, since Ruskin despised the style). The third story was removed, the fa?ade was covered in new brick, and the gothic arched windows were replaced with square models. In its original form it served as a bank, public auditorium, and a post office. However, a change to a single tenant on the ground floor, Worcester Gas Light Co., also required alterations to the fa?ade. Changes to the storefront made it easier to display items available for purchase inside the building.Additionally, the building was adapting to architectural trends. Gothic was out of style, but Classical and Colonial Revival were very fashionable.

Restoring the Bank Block to its Ruskinian Gothic beginnings would not only be financially infeasible, but would erase an era of the building?s history. However, this doesn?t mean that interpretive measures shouldn?t be taken to raise awareness of this building?s fascinating evolution. Like the surrounding neighborhood of Hyde Park, the Bank Block is evidence of a community?s inevitable growth, change, and adaptability. Uncovering meaningful stories such as these gives us insight into how the built environment evolves to meet new needs and realities of the communities who use them.