22 Sep 2023 A legacy of lumber lives on in Port Norfolk: the history of the A.T. Stearns Lumber Co.

HBI is revisiting the history of the Port Norfolk area in Dorchester as we consider the preservation of the last extant building from the historic A.T. Stearns Lumber Company. Currently owned by the Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR), the building at 98 Taylor Street in Dorchester was once the office or counting house of the influential A.T. Stearns Lumber Company from the mid-1800s until the company’s dissolution in 1968.

Known as Pine Neck in the 17th century, Port Norfolk was commercially and residentially undeveloped, with only a handful of families living there until the Old Colony Railroad extended through the area in 1844. The Port Norfolk area went on to attract a number of industries for its convenient location on the Neponset River and for the rail nearby.

From the Saw Mill to the Lumber Yard

The A.T. Stearns Lumber Co. was one of the first enterprises that contributed significantly to shaping Port Norfolk and made the area a hub for the lumber industry in New England. Albert T. Stearns was born in Billerica, MA in 1821. His father was a farmer whose ownership of a grist and saw mill introduced Stearns to the industry he’d later become a pillar within. In 1843 A.T. Stearns established the first lumber yard in Waltham, MA, selling it in 1849 and opening another along the Neponset River that same year. His lumber operations covered 40 acres in the Port Norfolk area. Stearns also established a saw mill in Apalachicola, Florida, called the Cyprus Lumber Company, which later served as a model for cypress plants across the region.

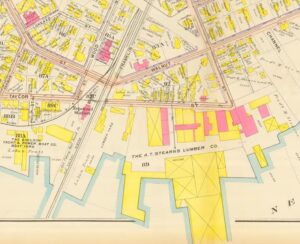

1910 Bromley Atlas identifies 98 Taylor as the “office” building in red to indicate that it was a brick structure. Note the wharf and the number of Stearns buildings along the Neponset that is green space today and a part of the Neponset River Greenway.

The building at 98 Taylor Street, which residents, community leaders, and organizations in Port Norfolk recently prevented from being demolished, is the only structure from the A. T. Stearns Lumber Co. to have survived modern development along the Neponset. The Greek Revival style brick structure dates to 1855 and is identified as an “office” in a 1910 Bromley Atlas, likely being the same “counting house” referred to in other historical records.

Photo taken by surveyors of MA Historical Commission in 1977.

Stearns specialized in wooden gutters, a necessary component in housing construction, and even invented a machine just for this purpose. Stearns’ machine removed the core of the gutter in one piece with a cylinder saw, which allowed the leftover product to be reduced into moulding, trim, ect. Pine was the preferred wood used for this at the time, until Mr. Stearns made some industry-changing realizations in the 1870s, whose results would see him dubbed the “Apostle of Cypress.”

An Advocate of Cypress

In 1871, Stearns was sent a sample of cypress that sat unused for years before he thought to utilize it to make the door frames and mouldings of a new office building. Afterwards, Stearns realized the potential cypress held as a finishing wood; it was inexpensive, more rot-resistant than pine, and came in a variety of rich hues.

Until Stearns’ fierce advocacy of cypress, “it was the pariah of the southern swamps; it was the nemesis of the sawmill man; it was the cap-and-bells of the dealers; it was the disgust of the American consumer.”

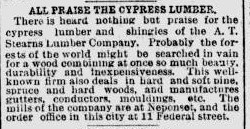

Published in the Boston Post in 1891.

But Stearns was confident in cypress and ardently encouraged its use in projects wherever he was involved. He was so sure of its success that he regularly 0ffered to make gutters from cypress for free, with the promise that he’d replace them with pine if they were not to his customer’s satisfaction. In a few years time, gulf cypress was an A.T. Stearns Lumber Co. special.

On the morning of September 25th, 1884 a fire broke out in the engine room of the A.T. Stearns complex. The Boston Daily Globe reported that “Before 8 o’clock the place was a mass of ruins, the only buildings standing being a part of the carpenter shop, a large shed, the boiler house and office. The two latter are brick buildings, with iron shutters.” Of those two brick buildings, the “office” that survived must’ve been 98 Taylor. Damage resulted in the loss of the wharf, stores of wood, and machinery that amounted to at least $200,000. But as the maps below illustrate, A.T. Stearns didn’t seem to have any issues with rebuilding.

1874 Bromley Atlas: A.T. Stearns Lumber Co. before the fire of 1884.

1904 Bromley Atlas: A.T. Stearns Lumber Co. 20 years after the fire.

We had hoped that 98 Taylor was the office building that Stearns experimented on with his cypress trim in the 1870s, but as we stated earlier, that building dates to 1855. Though that’s no reason to think that Mr. Stearns never introduced some of his early experimental cypress to that building. When HBI staff was onsite we took note of the crown moulding that had once been hidden above the drop ceiling, as it was the only observable historic fabric that could potentially be preserved.

While most interior moulding is crafted from pine, there remains the inclination to wonder if maybe this small detail could be the last remaining demonstration of cypress moulding in an A.T. Stearns building. The style of the trim is more ornamental than usual for an office space; Stearns may have been determined to display their mastery across the site, even down to the most minute details of their office building. Regardless of whatever type of wood the trim was crafted from, if it can be preserved throughout the rehabilitation process, it would lend a distinctively Stearns characteristic to the space.

An Industry Altered, An Enterprise Shuttered

Research to establish the cause of A.T. Stearns Lumber shutting down in 1968 did not lead us to one direct reason, but highlighted some historic developments in the national timber industry that would have had a great impact on the operations of the Stearns Lumber Co. in Port Norfolk.

In the late 1800s/early 1900s, a national forest reserve movement was taking shape with the federal government intervening to regulate and conserve the nation’s natural resources. We know that natural timber reserves around Apalachicola, Florida were dwindling by the 1920s due to constant logging for decades. Total national lumber production fell from 35 billion board feet in 1920 to 10 billion in 1932. Couple this with the Great Depression, an increase in the use of cement and steel, and the increasing expense of transporting timber as logging expanded far beyond the waterways that were originally convenient for this purpose, and it’s clear that these shifts could be insurmountable for some northeast lumber companies.

The final insurmountable “cherry-on-top” could have been the floods of 1968. Across the U.S., new 24-hour precipitation records were met in March 1968, with Eastern MA being one of the worst hit areas. The Dept. of Interior reported flood heights of 14.65 and 8.18 feet high in Norwood and Canton, MA, respectively. Flood heights could not be recorded for the Hyde Park area of the Neponset River, which would give us the closest measurement for the Port Norfolk area. The Corps of Engineers estimated that losses in MA, mostly commercial, amounted to approximately $28 million. The flood damage that likely occurred at the A. T. Stearns Lumber Co. in 1968, could have been crippling after decades of enduring a struggling timber industry.

Corner of Water and Taylor Streets, 1965

Contributor: George Bowers, Courtesy of the University Archives & Special Collections Department, Joseph P. Healey

Library, University of Massachusetts Boston: Mass. Memories Road Show collection.

The Port Norfolk area was claimed by the state in 1986 and has been transformed from its industrial past to protected green space by the DCR and the Neponset River Watershed Association. The Neponset River Greenway trail provides a 13-mile respite from city life, connecting the communities of Dorchester, Hyde Park, Mattapan, and Milton. The trail extensions along the nearby Tenean Beach were completed in 2010, and the extensions along the Port Norfolk area were completed in 2015.

Just north of the Neponset park that borders Taylor Street, is the Joseph Finnegan Park, which was opened in 2017 and is named after the senator that represented Dorchester in the House of Representatives and the State Senate during the Great Depression. A bit farther north, a new development is currently underway at 24 Ericsson Street. At the site of another Port Norfolk-shaping company, where the General Isaac Putnam Nail Company once stood, a new housing development is in progress. The new “Neponset Wharf,” planned and put forth by RISETogether, will have 120 new housing units, some retail/office space, and will include the restoration of the salt marsh.

As a collective, Port Norfolk is emerging from its industrial past, and moving towards a greener future with adaptive reuse, conservation, and climate resiliency in mind. Historic Boston Inc. looks forward to playing a role in the transformation of Port Norfolk, hopefully preserving the legacy of the “Apostle of Cypress” along the way.

Port Norfolk today. 98 Taylor Street is identified by the red arrow.