January 8, 2018 The Legacy of Publishers Ticknor and Fields at the Old Corner Bookstore, Part 3

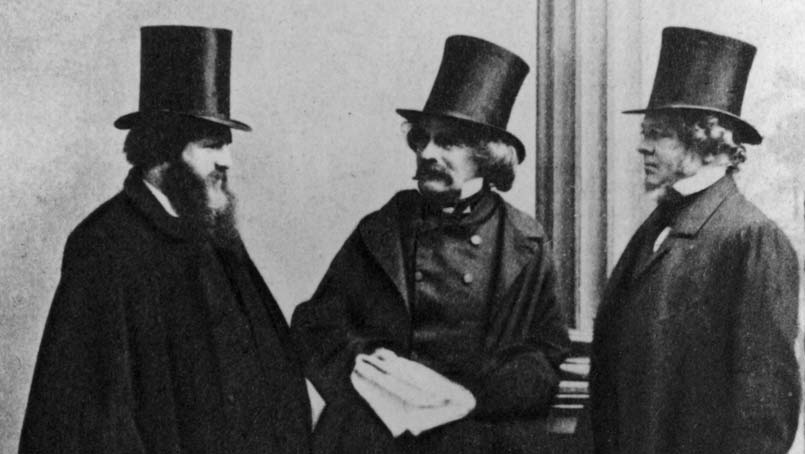

le“Hawthorne and His Publisher”

Literary historian Rob Velella recently spoke at the Old South Meetinghouse on the extraordinary history of Ticknor and Fields whose 19th century publishing hegemony made the Old Corner Bookstore one of the most importance places in American literary history. Rob graciously permitted HBI to re-print his remarks. This is the third of four installments.

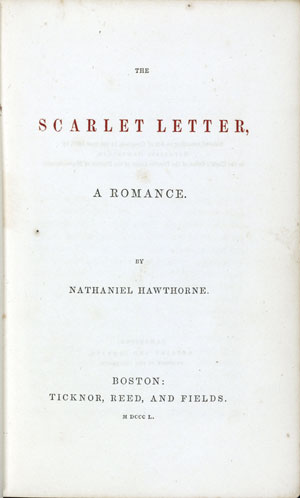

Publisher James T. Fields actually claimed a fairly large amount of responsibility in inspiring the work that is considered Nathaniel Hawthorne’s masterpiece.

Most of Hawthorne’s early literary career was a failure, with short stories published in poorly circulated magazines and annual gift books, many of which never paid him. Many of his stories were published anonymously, and the author complained he was the most obscure man of letters in America. In 1849, amidst the political controversy over Hawthorne’s removal from his job at the Salem custom house, Fields traveled to Salem to meet him. He asked Hawthorne if he had been able to write anything during his time at the custom house, but Hawthorne said he hadn’t. The job dulled away his creativity and, further, he asked, “Who would risk publishing a book for me, the most unpopular writer in America?” I would, Fields responded, and offer a minimum print run of 2,000 copies of whatever he had. Hawthorne insisted, however, that he had nothing.

But as Fields turned to leave, Hawthorne offered him a manuscript which he said was “either very good or very bad, – I don’t know which.” Fields read the manuscript on the train ride home to Boston. He took the first train the next morning to Salem. He had just read The Scarlet Letter and wanted to publish it immediately. He offered an impressive first print run of 2500 copies and a higher-than-average 15 percent royalty. It was extremely successful and a second edition was issued two weeks after the first. It was Hawthorne’s first novel as a mature writer, and it was Fields that made it happen.

But as Fields turned to leave, Hawthorne offered him a manuscript which he said was “either very good or very bad, – I don’t know which.” Fields read the manuscript on the train ride home to Boston. He took the first train the next morning to Salem. He had just read The Scarlet Letter and wanted to publish it immediately. He offered an impressive first print run of 2500 copies and a higher-than-average 15 percent royalty. It was extremely successful and a second edition was issued two weeks after the first. It was Hawthorne’s first novel as a mature writer, and it was Fields that made it happen.

Well, so recalled James T. Fields; Hawthorne’s wife Sophia Peabody would later dispute how large a role Fields played. Either way, Fields was certainly a catalyst to several authors over the years. And both Fields and Ticknor were both important sources of encouragement specifically to Hawthorne, who frequently suffered from writer’s block and questioned his own literary worth. To Fields, he noted, “I care more for your good opinion than for that of a host of critics, and have excellent reason or so doing; inasmuch as my literary success, whatever it has been or may be, is the result of my connection with you.”

As glowing as this praise is, Hawthorne seems to have been more personally loyal to William Ticknor. Ticknor was only four years younger than Hawthorne, compared to the 13-year difference with the much-younger Fields. During the Civil War, Hawthorne asked Ticknor to accompany him to Washington, D.C. to see the effects of the war firsthand. The trip inspired the essay “Chiefly About War Matters,” which James T. Fields printed in the Atlantic Monthly, which he was then editing. But Fields censored the essay. Among Field’s complaints was Hawthorne’s description of President Abraham Lincoln, who Hawthorne referred to using terms like “coarse,” “sly,” and “queer” – terms of endearment, in context, but Fields worried how people would respond to criticism of the President during wartime. Hawthorne agreed to the changes, but privately complained, writing, “What a terrible thing it is to try to let off a little bit of truth into this miserable humbug of a world!”

In 1864, when Hawthorne was in a funk and feeling ill, William Ticknor took him on a trip south as far as Philadelphia. Hawthorne, who worried he was dying, was cold that night and Ticknor offered him his coat. Ticknor caught a cold and died the next morning. Hawthorne was devastated. When he returned to Concord, Massachusetts, he walked from the train station back to his home The Wayside. His wife described his sudden and surprising appearance: “As soon as I saw him, I was frightened out of all knowledge of myself – so haggard, so white, so deeply scored with pain and fatigue was [his] face.” He had rushed to get home to his wife, “where he could fling off all care of himself and give way to his feelings, pen up and kept back for so long,” especially his feelings over Ticknor. The friendship of Hawthorne and Ticknor was strong enough that Ticknor’s daughter Caroline later wrote a book about it called Hawthorne and His Publisher in 1913.

After the death of Ticknor, James Fields immediately took the senior role at the publishing house. Fields was essential for giving the identity of the house of Ticknor & Fields as a literary publisher – not just a publisher of books, but of quality literature meant to stand the test of time. Fields also was a bit of an opportunist. After the death of Henry David Thoreau, Fields bought those unsold copies of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack River, tore off the title page, and printed a new one with the Ticknor & Fields imprint and sold it as a new “second edition.” But Fields knew good quality literature – for the most part – and did what he could to seek out and endorse the best of the best.

And perhaps that was also the undoing of Ticknor & Fields.

Fields was charming and likeable and he easily made friends. He was himself a poet, which earned the respect of other writers. He was connected with critics and editors like Edwin Percy Whipple, Samuel Goodrich, and Rufus Griswold – each of whom had tremendous standing in early American literature. Fields knew everyone – he helped introduce Herman Melville to Oliver Wendell Holmes and Nathaniel Hawthorne, for example – and reading any of his extant letters is like lending an ear to the latest literary gossip and name-dropping of the era. The company also was the first to offer payments to foreign authors in order to print their works – a kindly gesture that was not legally required in the era without international copyright protections for authors. By 1856, they were the official American publishers of Alfred, Lord Tennyson, for example, and each edition included a quote from a letter from the poet acknowledging that Ticknor & Fields alone were authorized to print his works in the United States.

Fields did whatever it took to urge his writers to work hard– sometimes going too far. With Hawthorne, in 1863 and 1864, he paid him in advance, suggested a title, and published an announcement of his forthcoming work – all without Hawthorne agreeing. Hawthorne never finished that particular work, and Fields ended up placing the incomplete manuscript on Hawthorne’s casket during his funeral, where Fields actually served as a pallbearer. Not long after, Hawthorne’s widow Sophia Peabody threatened to sue Fields because the company had promised “to pay the highest rate of copyright it ever paid” in royalties, and she felt he stiffed her. The story is just to emphasize that Fields always did what he thought was best to push his authors. And he often did whatever it took to keep them happy. For Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, for example, he threw parties in his honor and bought him concert tickets. And, of course, he kissed up: “It strikes me the author of ‘Evangeline’ does better and better every time he strikes the lyre,” he once told Longfellow. When negative reviews were published, he would write to his authors and reassure them the critic was wrong – and he might even threaten to boycott that critic. His loyalty – and his generous royalties – certainly did well for the company.

Next: Ticknor & Fields After the Old Corner Bookstore