October 30, 2023 “This was when there were slaves in Boston”: HBI Founder John Codman acknowledges his ancestor’s enslavement of Black Bostonians

It has come to the attention of Historic Boston Inc. that the family of our organization’s founder, John Codman, had a personal connection to the enslavement of Black Bostonians in the 18th century. We stumbled across this information by chance, as the newest member of HBI, our Office Manager Erika Tauer, set about acquainting herself with HBI’s founding history and mission.

Join Erika as we acknowledge our founder’s connection to the 1755 trial and execution of two enslaved individuals who had been accused of poisoning their enslaver.

A Coincidental Realization

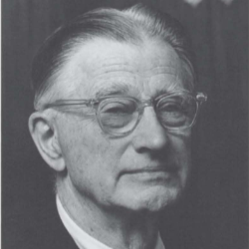

As a lover of print and personal records, I chose to start my exploration of HBI’s history with the 1983 transcript of an interview with HBI founder John Codman, recorded the year prior in 1982. Codman was born in 1899 and died in 1989, so he would have been 83 years old at the time this interview was conducted.

Oral history was still in its infancy as a methodological practice in the 1980s, having been birthed from the 1960s academic determination that history should take a more social approach, centered on everyday people. Best practices and strategies for keeping your informant specific and on topic during an interview were still being established. In an attempt to supply an approximate date/era for each generation to anchor Codman’s ancestral narrative, I have incorporated a general timeline, informed from sources pertaining to the Rev. John Codman (1782-1847), and John Codman III (1755-1803), whom John Singleton Copley had famously painted around 1800. However, some eras have been tricky to pin down and we are left only with what John Codman, himself, had to say on the matter.

Interviewed by Stanley M. Smith, then HBI’s Executive Director, Codman begins his oral history with a description of his ancestry, which he knew about from genealogical research his cousin had conducted. He stated that the first of the Codmans had lived on Martha’s Vineyard, and that a son, Stephen, was the family member who had moved to Charlestown–where the Codman family would reside for several generations. Without going to the archives personally, my research did not take me this far back in time. We can assume that the first of the Codman’s likely landed on the shores of Martha’s Vineyard (what the native Wampanoag would have called Noepe) in the mid 1600s, and likely moved to Charlestown about the early 1700s.

John Codman notes that he refused the title “John Codman the Third” as he already had a grandson with the name. He goes on to state that his great grandfather was the Reverend John Codman (1782-1847), who had a congregation in Dorchester, and for whom Codman Square was named. The Reverend had been the first minister at the Second Church, preaching from 1808 until his death in 1847. President John Adams was known to occasionally attend the Reverend’s “fire and brimstone” sermons.

Codman adds that there was a break in the continuity of the “John Codmans,” as a segue into his grandfather William Codman’s story. The grandson of the Reverend was William C. Codman who worked in the insurance business until the Great Fire of 1872 left them bankrupt. It was at this juncture in time that the Codman family set their sights on the real estate business. Nevertheless, he continues to paint the trajectory of his ancestral history, including that there were two other John Codman’s prior to the Reverend; the Reverend was the son of the “Honorable John” (1755-1803) who had served in the House of Representatives (1796-1798) and as a Massachusetts State Senator from 1800 until his death in 1803. It would seem that the “Honorable John” was the enslaver John Codman’s son. Of them Codman said: “One of them had a hard time, he must have been a pretty tough guy because his slaves, he evidently didn’t treat them well because they successfully poisoned him. This was when there were slaves in Boston.”(3) And thus, Codman revealed that his great, great, great grandfather had been an enslaver.

Suddenly, the realization struck that I had read the name “John Codman” somewhere and it wasn’t until he acknowledged this unpleasant chapter of his ancestral history that it dawned on me where I had read it.

Prior to joining HBI, I was working as Administrative Coordinator for Old North Illuminated (ONI). My time with ONI happened to occur the same year they brought on the wonderful historian, Dr. Jaimie Crumley, as their Research Fellow, whose work sought to incorporate the stories and experiences of Black and Indigenous Bostonians connected to the Old North Church into the interpretive narrative of the site. It was an episode of Dr. Crumley’s research series, Illuminating the Unseen, that highlighted the 1755 story of Mark, Phillis, and Phebe–enslaved Bostonians who had poisoned their enslaver John Codman.

We encourage you to watch or read through Dr. Crumley’s Illuminating the Unseen series; her research has contributed a vital perspective, long absent from the history of Old North, the North End, and the City of Boston. Illuminating the Unseen was honored this month, along with HBI’s Upham’s Corner Comfort Kitchen, as a winner of the Boston Preservation Alliance’s 2023 Preservation Achievement Award.

Slavery in 18th century Boston

Dr. Crumley became aware of this incident after reading a 1798 letter Paul Revere wrote about his “Midnight Ride” on April 18th, 1775 from the Massachusetts Historical Society. Describing his location Revere writes: “After I had passed Charlestown Neck, [and] got nearly opposite where Mark was hung in chains, I saw two men on Horse back, under a Tree.”

Historian Jared Ross Hardesty’s “Negro at the Gate”: Enslaved Labor in Eighteenth Century Boston,” gives a glimpse into the socio-economic conditions that shaped the lives of Mark, Phillis, and Phebe as unfree laborers in the Atlantic World, of which 18th century Boston was a pivotal part. Hardesty states: “Enslaved Black [people] in Massachusetts were the main source of bound labor and outnumbered any other type, including apprentices, indentured servants, and Indians.” Estimates suggest that enslaved Black Africans consisted of 10-15% of Boston’s 18th century population.

Boston’s mercantile economy relied on skilled labor like blacksmiths, shipbuilders, printers, etc. Unlike apprentices or indentured servants, who could eventually use their specialized skill for personal benefit once their contract expired, the skills of an enslaved person would benefit their enslavers across their lifetime. And so it was viewed as an investment in property to have a slave skilled in a craft. Hardesty describes Boston as “an Atlantic port reliant on a variety of forms of unfree labor.” In the 1883 revisitation of this trial, it was noted that Codman employed enslaved individuals as “mechanics, common laborers, or house servants.” The trial transcript itself reveals that Phillis and Phebe were house servants, whose task of food preparation presented the opportunity to dose Codman with the poison acquired by Mark.

Hardesty states: “Using labor as a lens to explore how this society shaped the lives of slaves and other marginal people suggests that autonomy and the opportunity to enjoy the fruits of their labor were more important to these individuals than were abstract notions of freedom or emancipation.” These modest aspirations are what drove Mark, Phillis, and Phebe to poison ship captain and merchant John Codman in 1755. In later testimony, Phillis stated that Mark had “said that Mr. Salmon’s [slaves] had poison’d him, and were never found out, but had got good masters, & so might we.” And so they took this risk, for the chance to possibly live easier lives working for “good masters.” Not for our modern ideals of freedom and justice that were far removed from their lived reality.

Acting for Improved Circumstances

Mark was found to have procured the poison (likely arsenic) from apothecaries around Boston. Mark mentions that he had obtained the poison from two men who were enslaved by the owners of apothecaries. One such source was Dr. William Clarke’s apothecary in the North End. The Old Corner Bookstore had been an apothecary at this time as well, so we wonder if a transaction of substances may have put poison from the Old Corner into Mark’s hands. The irony of supplies from this building being used to kill the ancestor of the man who would save it in 1960 being too tempting to not consider.

Phillis, who states in her testimony that she had been enslaved by Codman since she was a little girl, had been the one to fatally lace Codman’s food. Phebe, who had given lesser doses of poison, was spared execution to live as an example. In the transcript of Mark’s “Last & Dying Words,” he states that Codman had allowed him to live in Boston with his wife. In Phillis’ testimony she explains that Mark had proposed to poison Codman “a week or a Fortnight after my master brought him home from Boston…” Hardesty speculated that Mark may have been prohibited from staying with his wife in Boston, and Codman, calling him back to Charlestown, may have provided him with a motive.

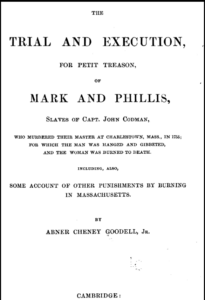

The 1755 trial and execution of Mark and Phillis was reprinted in 1883, and is accessible in the Library of Congress’ digital collections. Mark and Phillis were executed on September 18th. Mark was hanged, Phillis was burned at the stake, and Phebe was transported to the West Indies, taken away from her husband Quaco, where she likely toiled under the cruelties of the Caribbean plantation system for the remainder of her life.

Disclaimer: The following paragraph contains graphic details about Mark and Phillis’ sentencing and execution.

The trial and execution of Mark and Phillis “is the only known instance of the infliction of the common law penalty for petit treason in Massachusetts.” Rather than charge them with murder, for which the penalty was hanging, they were charged with petit treason. Petit treason was an offense in which a person killed or otherwise violated the authority of a social superior; this offense was applied to the murder of a husband by a wife, a member of the clergy killing a superior, or an enslaved person murdering their enslaver. In these cases, it had less to do with the murder, and more to do with the fact that these individuals had defied a social superior. But the punishment for petit treason was far more cruel than that which was meted out for murder. It required the convicted to be “drawn to the place of execution,” in which they were tied to a horse and pulled to the site. Later, sleds for the convicted to lay upon were used for this purpose; to lessen the suffering or to prolong their survival to the execution site, we don’t know. The desecration of their bodies after execution was also a part of customary punishment. It was not specified that Mark’s body should be gibbetted in his sentence, but we know that it was and he hung there for decades. Had it been murder he was convicted of, his body would have been buried the day after execution. It was the denial of the convicted’s humanity that set the punishment of murder and petit treason apart.

Nearly 50 years later, Revere references the site of Mark’s execution as a geographic marker that had remained culturally relevant. Mark’s body hung in a gibbet on Charlestown Common for nearly 20 years and his last words were published and sold next to a prison on Queen Street. His body and last words, immortalized in print, would serve as a terrorizing reminder to the enslaved population of Boston of what the cost of resistance would be. Even while their white counterparts were actively organizing to free themselves from the rule of the British monarchy.

The Unfreedom Trail

As the City of Boston and the historic sites along The Freedom Trail have started to contend with our region’s role in the enslavement and trafficking of Black and Indigenous peoples, it is important to understand that the oppression of our fellow man occurred in tandem with those rose-colored narratives of the Revolution that many know our city by. It is important to ensure that when we tell these stories of Boston, that visitors to our city understand that enslaved laborers were a part of every aspect of colonial life and the creation of this city. This is why there is added weight to John Codman’s supplementation that “This was when there were slaves in Boston,” because too often they are left out of these national narratives. They were “the diggers of basements and wells, the pavers of streets, the cutters and haulers of wood, and the carters of everything that needed moving…they may not have contributed to the eradication of slavery as an institution, but they did have a role in shaping [our] towns.” Hardesty concludes that skilled enslaved individuals recognized their value and “began setting limits and manipulating the terms of his or her slavery, in effect redrawing its boundaries.”

John Codman was ahead of his time in the way he acknowledged his ancestors’ history, one that many would have preferred to leave off the record. At the beginning of his interview, he told an anecdote in which he deduced: “I’m more sorry over the things that I don’t say than the things that I say. I’m more likely to say them now, I’ve grown bolder since I’ve grown older.”

We hope the same is true of Boston.

References

Goodell, Abner Cheney. “The trial and execution for petit treason, of Mark and Phillis, slaves of Capt. John Codman: who murdered their master at Charlestown, Mass., in , for which the man was hanged and gibbeted, and the woman was burned to death: including, also, some account of other punishments by burning in Massachusetts.” [Cambridge, Mass.: J. Wilson, 1883] Pdf. https://www.loc.gov/item/2001615796/.

Jared Ross Hardesty, “Negro at the Gate”: Enslaved Labor in Eighteenth Century Boston,” Vol. 87, No. 1, March 2014.The New England Quarterly 87, no. 1 (2014): 72–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43285054

“The English capital crime that’s still on the books here, even though it’s a remnant of our slave days and nobody’s been tried for it since 1782.” (2020). https://www.universalhub.com/2020/english-capital-crime-thats-still-books-here-even

William J. Walczak, “Codman Square: History (1630 to present), Turmoil (1950-1980) and Revival (1980-2000): Factors which lead to Racial and Ethnic Placement, Racial Segregation, Racial Transition, and Stable Integration.”

https://www.codman.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CodmanSquareHistory.pdf