26 Aug To cook or not to cook: Dorothy Clark on Fannie Farmer and her Boston Cookbook

I am fascinated by people who are fascinated by food and cooking it. While I enjoy eating periodically, I have no interest in and little time or energy for all that preparing food entails. Also, I’m rather proud of the fact that I am uninitiated in the ways of cookery. As my family members like to quip, “She doesn’t do heavy equipment; that includes the stove.” I’m more inclined to spend time in my kitchen concocting useful elixirs, such as those taught in the core Potions class at Hogwarts School of Witchcraft and Wizardry. My lack of kitchen experience is what makes me simultaneously the worst and the best person to write about 19th-century culinary maven Fannie Farmer and her famed food tome, The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook, first published in Boston in 1896.

In more than 600 pages—about 20 of which at the end of the book are devoted to national and local advertisements for cookware and ingredients for making food such as King Arthur Flour Company, Stickney & Poor Spice Co., and Knox’s Sparkling Calves-Foot Gelatine—Farmer gives thorough instruction in the science and art of cooking. The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook has everything you could imagine eating, along foods you might not want to think about ingesting. It’s all there, from soup to nuts, or, to borrow an even older idiom, ab ovo usque ad mala, a Latin phrase courtesy of the poet Horace that translates to “from egg to apples.” It refers to the first and last foods of a Roman several-course meal.

As I noted earlier, I do on occasion enjoy eating. However, there are several recipes Farmer offered in the cookbook that could never whet my appetite. Take terrapin, for example, which, along with frogs, Farmer writes, “belong to a lower order of animals than fish,—reptiles. They are both table delicacies, and are eaten by the few.” Still, Farmer guides cooks in the unappetizing details of preparing both dishes; cooking terrapin is particularly excruciating for both cook—about an hour of prep time and a strong constitution are needed to ready this lowly creature for use in one of the three recipes she provides—as well as the latter, which “should always be cooked alive.” For those who perhaps could neither afford terrapin or stomach its preparation there was mock turtle soup. The fact that this called for boiling a calf’s head may not be especially palatable today, but at least the calf didn’t have to be alive.

With my penchant for sweets, I found Farmer’s dessert recipes far more comforting. Cookies, cakes, pies, pastries, jellies, confections, ice creams, hot puddings, cold desserts—the choices are astounded. I would consider trying one or two of those recipes, if I didn’t spend most of my time reading and writing.

Farmer didn’t stop at mere recipes. Her guidance includes a variety of menus for breakfast, luncheons, and dinners as well as Thanksgiving and Christmas meals. And there’s a full-course dinner menu calling for 12 courses, with the option to simplify this by eliminating the third, seventh, eight, and tenth courses, as well as the game typically served in the ninth course.

Farmer was intense about the science of her subject. As in domestic science, the 19th century saw the principles of science emerging in a variety of activities and areas of thought. This fit well with the “cult of true womanhood,” a Victorian-era ideology that emphasized women’s roles in the home and their responsibility for creating and maintaining an ideal family environment. Largely ascribed to and subscribed by middle-class white women, the notion of “true womanhood” emphasized the ultimate in femininity, purity, gentility, and perfection in household management, among other idealistic and unrealistic values and qualities. Being a superb cook, keeping a clean and well-ordered home, and rearing children who would grow up to be useful members of society were the hallmarks of the “true woman.”

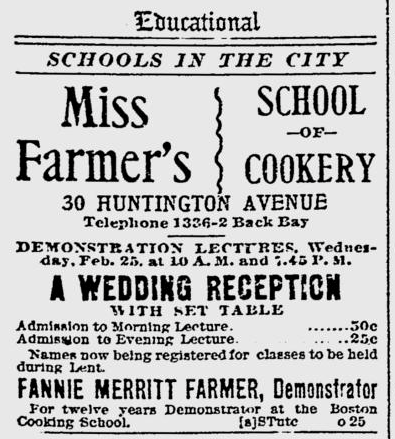

Farmer gives her readers the basics about the science of food, stressing that anything that nourishes the body is food, calling for the precise measurement of ingredients used as well as optimum timing in cooking. Imparting information such as the nutritional value, in scientific terms, shows her to be a well-studied expert in command of an impressive body of knowledge. Just how did she acquire her expertise? Born in Boston in 1857, Fannie Merritt Farmer grew up in Medford with her parents and three younger sisters. She would have gone to college, but a stroke at the age of 16 rendered her unable to walk so she remained at home, cared for by her parents. In her period of convalescence, Farmer devoted her energies to cooking and got really good at it.

Farmer regained the ability to walk, though with a marked limp, and when she was 30, she enrolled at the Boston Cooking School. This affordable institution was established in 1879 by the Women’s Education Association for the purpose of offering instruction to those who wanted to earn a living cooking, “or who would make practical use of such information in their families.” Farmer graduated from student to assistant principal and became principal in 1891, becoming the toast of the culinary profession, publishing her cooking and domestic reference book in 1896 and taking her demonstrations on the lecture circuit.

The name Fannie Farmer is not to be confused with that of the Fanny Farmer candy shops, though that, I now realize, is how I actually came to know the name and to associate it with edible stuff. But Fannie Farmer and Fanny Farmer are linked only by pronunciation; the Fannie of the cookbook had nothing to do with the candy store Fanny. Clearly, Canadian businessman Frank O’Connor knew the value of branding when he started his candy company in 1919 in Rochester, N. Y., four years after cookbook Fannie’s death. While he changed the spelling of Fanny to Fannie, the sound of the names remained same thus solidifying their linkage. Clever marketing, and O’Connor’s candy tins and boxes even bore an image of someone who looked like she ought to be Fannie, even if it isn’t really her. O’Connor’s enterprise grew to 400 shops, primarily in the northeast. Corporate acquisitions and such eventually diminished the Fanny Farmer candy store presence.

Still in print, the 13th edition of Farmer’s book was published in 1990 and reissued in 1996 to celebrate its centennial. For the later editions, the title was changed from The Boston Cooking-School Cookbook to include Farmer’s name and is more simply called The Fannie Farmer Cookbook. This edition is greatly expanded, at 1,231 pages. It doesn’t appear to have any terrapin recipes. Nor does it have the chapter that Farmer included in the 1896 edition titled “Helpful Hints to the Young Housekeeper,” which no doubt was designed to ensure that readers received everything they needed to become well-rounded homemakers, a stage that I bypassed quite some time ago. However, I did find her instruction for cleaning piano keys (“rub over with alcohol”) to be extremely useful. I’m going to go do that instead of trying out a recipe.

Hungry for more? Check out the video “Fanny’s Last Supper” by Chris Kimball from Milk Street.

Dorothy A. Clark grew up in Boston and has lived in Jamaica Plain since 1985. Her love of old houses became a passion for historic preservation when she joined the group of Brookline and JP residents who fought to save the Pinebank Mansion on Jamaica Pond. Although the group’s efforts were not successful, Dorothy discovered that she wanted to be involved with the stewardship of historical and cultural resources. A full-time journalist in her previous career, Dorothy worked for the Boston Globe and the Boston Herald for more than two decades as a copy editor, and wrote feature stories as well as music and book reviews. She is a member of the Board of Directors of the Loring Greenough House in JP and an adjunct faculty member at the Boston Architectural College. She currently works as editorial services manager at Historic New England and is editor of Historic New England magazine.