17 Apr 2024 What Should the Old Corner Bookstore Look Like? Part 1: John Perkins Brown

Architect Chris Scovel, a guest blogger from MASS Design Group, lends his expertise to illuminate the architectural history of the Old Corner Bookstore. MASS Design Group has been contracted to lead HBI’s rehabilitation of the OCB complex, and the answer to “What should the Old Corner Bookstore look like?” will inform our joint approach to envelope restoration.

With over 300 years of history layered upon it, this once simple question has become increasingly difficult for successive generations of Old Corner Bookstore caretakers. Anne Hutchinson’s 1634 home, on the corner of what is now School and Washington Streets, had burned in 1711. In 1718 Thomas Creese (often also spelled “Crease”), an apothecary, built his home and business in its place; this corner building – the Creese House – is the oldest portion of what is now known as the Old Corner Bookstore, or OCB.

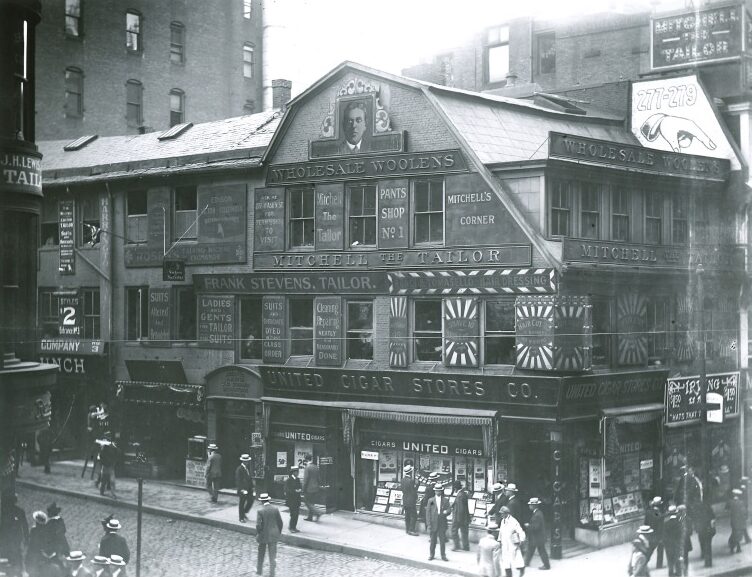

In 1937 – not so long ago for the Old Corner Bookstore – John Perkins Brown had an answer to this question. As a young architect in Boston, Brown knew an OCB covered with what he may have viewed as crass and unkempt advertising for the businesses within. This was a legacy of the nineteenth century in which a string of publishers, booksellers, tobacconists, tailors, and many other commercial tenants covered the building with the then equivalent of pop-up ads targeted at passing pedestrians. Beyond this, cumulative alterations to the buildings over the years had resulted in utilitarian roof lines and glazed storefronts at street level, as well as shed dormers and skylights which brought much needed daylight to its interiors.

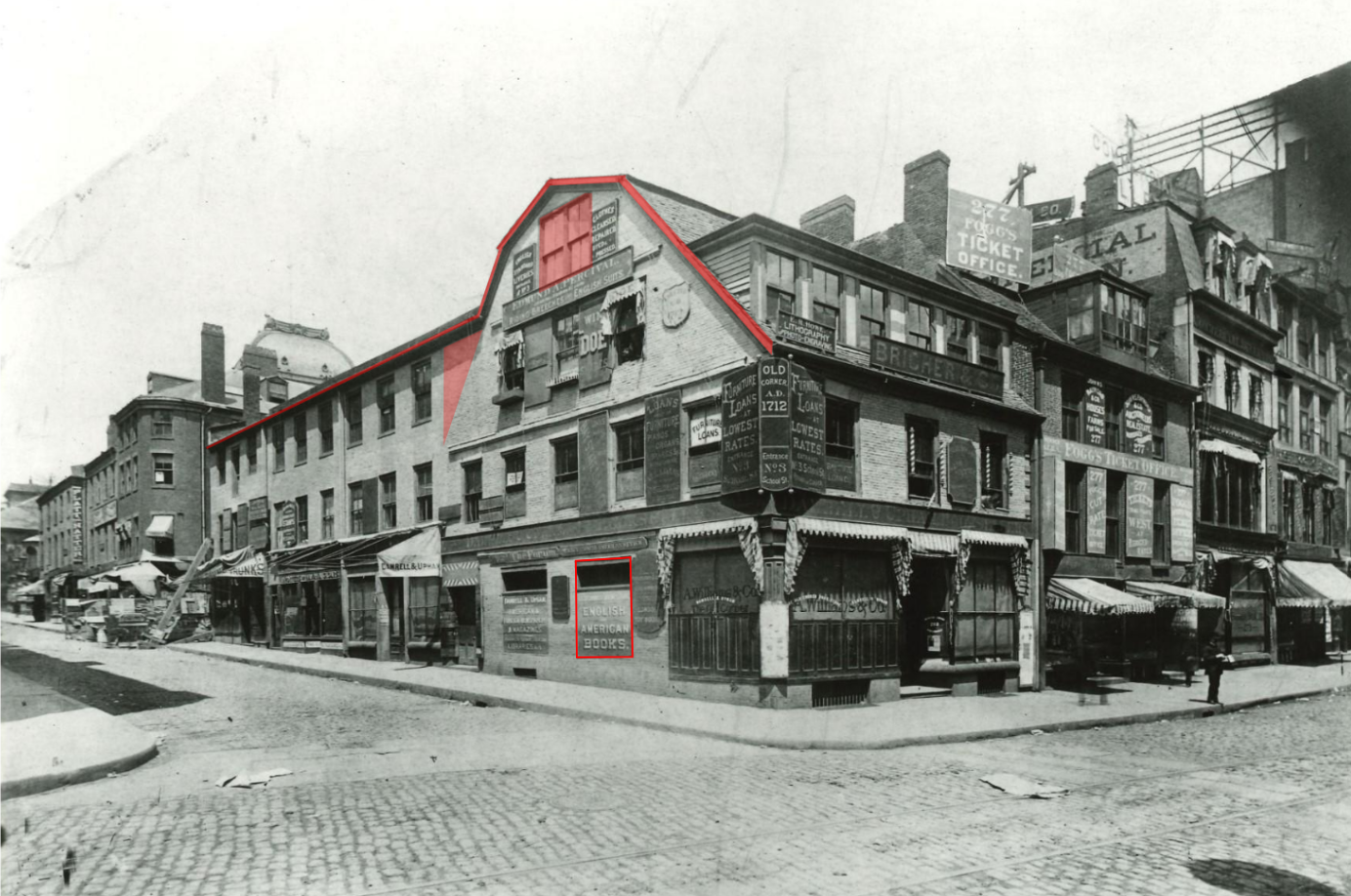

Brown would have understood that when 5-7 School Streets were built in 1827 directly adjacent to the 1718 Creese House’s gambrel roof, the west side of the gambrel roof was altered for a very sensible reason: to keep rain, snow, and ice from collecting where it would cause trouble. The new 1827 roof line was extended to meet the sloping 1718 roof. The triangle-shaped space beneath this roof extension was patched with a new brick wall flush with the adjacent new and old brick. A portion of the 1718 roof rake – the sloping wooden trim at its edge – was removed at this time, since it conflicted with the new 1827 brick triangle.

Standing on the opposite School Street sidewalk and looking up at the peak of the gambrel roof, Brown would have noticed that it was distinctly to the left of the center of the windows below and off-center in the building’s elevation. An atypically large 4th floor window exacerbated this asymmetry. (Brown later explained that sometime before 1865 a large first floor shop window was repurposed and installed on the 4th floor. Perhaps this was done to improve daylighting for office workers.) It’s not hard to imagine a young preservation-minded architect in the 1930s being troubled by the site of this incongruously large window asymmetrically situated at the most prominent point of the Creese House

In November of 1936 a fire damaged the upper stories of the Thomas Creese House, as well as the adjacent School Street buildings. The destructive fire and the initial construction work to repair it exposed building structures previously hidden, and Brown, and SPNEA (presently Historic New England) president William Sumner Appleton, took the opportunity to search for clues about the Creese House’s colonial history. (In 1940 Brown and Eleanor Ransom published a wonderful little book about these investigations.) Brown and Appleton also advocated for the salvage and reuse of the original Creese House brick, and for restoration work that re-created its 18th century masonry details. Bostonians owe them a debt of gratitude for this.

In 1937, reconstructing the upper stories of the fire damaged buildings, Brown or his contemporaries apparently revised the School Street roof line, the asymmetric gambrel roof, as well as the size and detailing of some masonry window openings, such as the one mentioned above. Today we still see these changes, which were made to evoke the colonial history of the building that Brown had studied. This is where things start to get interesting for the architecture nerds among us. Once again: What should the Old Corner Bookstore look like? Brown had an answer.

Old Corner Bookstore Buildings, 1880s. Highlighted in red are the 1827 roofline and triangular brick infill, as well as the asymmetric 4th floor window.

Brown re-established the full gambrel roof line of the 1718 Creese House and evoked it’s original massing with a few deft moves: he stopped the roof eave of 5 School Street short of the gambrel roof; he rebuilt the requisite masonry triangle, but recessed it a few inches behind the plane of the adjacent masonry walls in order to create a vertical corner and shadow line at 5 School Street; he rebuilt the rake of the gambrel roof, but as superficial wood construction on top of the masonry wall; and lastly he installed quoining to mark the west edge of the colonial building, quoining which had been removed in 1827 since it was no longer needed to structurally or visually reinforce the south west corner of the Creese House. The asymmetry of the gambrel roof, and the atypically large 4th floor window were also corrected.

These alterations were a success and the south face of the Creese House much more closely resembled the colonial facade. But in evoking something old, Brown created something entirely new: an OCB that is self-consciously curating, editing, and presenting its own history. Arguably, and ironically perhaps, the building resulting from his efforts at historic restoration had never before existed in history: a Creese House with a fully delineated gambrel roof sharing a party wall with visually distinct 1827 buildings, a 20th century amalgamation of 18th and 19th century structures. He did this in ways that required the artifice of, just for instance, installing boards against a brick wall to simulate the rake of a gambrel roof that no longer existed. Today, these sorts of things make an architect trained in the vestiges of the modernist tradition start to feel a little queasy.

There’s more than one answer to the title question of this post. In our next installment the OCB will be rescued once again – but this time in 1960 by HBI, which has its own thoughts about what it should look like.