18 May 2016 Streetcar Suburbia and the Fowler Clark Epstein Farm

Today the Fowler Clark Epstein Farm stands on a half acre of land, seemingly small for a farm plot, but a rarity in an urban setting such as Mattapan. Sandwiched between tightly packed triple-deckers and apartment complexes, it is a wonder that the farm that once sprawled across 35 acres in Dorchester still stands.

Built in 1786, while it had diminished in size, to 11.25 acres and then just under an acre, the Fowler Clark Epstein Farm remains among the earliest, intact, vernacular examples of agricultural properties in Boston and in urban centers across the Commonwealth. So how did the farm retain its historic character? Or rather under what circumstances was it able to remain largely undisturbed by an ever-changing and growing city?

Rita Walsh, Senior Preservation Planner, with Vanesse Hangen Brustlin has been assisting HBI with state and federal tax credit applications to support the rehabilitation of the Fowler Clark Epstein Farm property, and she is also preparing a nomination of the property to the National Register of Historic Places. In Part One of her application to the National Park Service, she provides a higher level of insight into this question.*

The advancement of public transit in the mid and late 19th century and the 1870 annexation of Dorchester to the City of Boston culminated in the transformation of Dorchester from an agricultural town to a streetcar suburb. Ms. Walsh notes that while large parcels of land were subdivided and developed, the landscape of Dorchester did not change all at once, She writes that, “the areas closest to the public transportation were typically developed earliest. Mattapan, in the southwest area of Dorchester, was one of the last areas of Dorchester to be developed, due in part to fewer public transportation improvements in the area and its distance from them. Norfolk Street near the Fowler Clark Epstein farm retained its large lots, uneven development through the 1880s.”

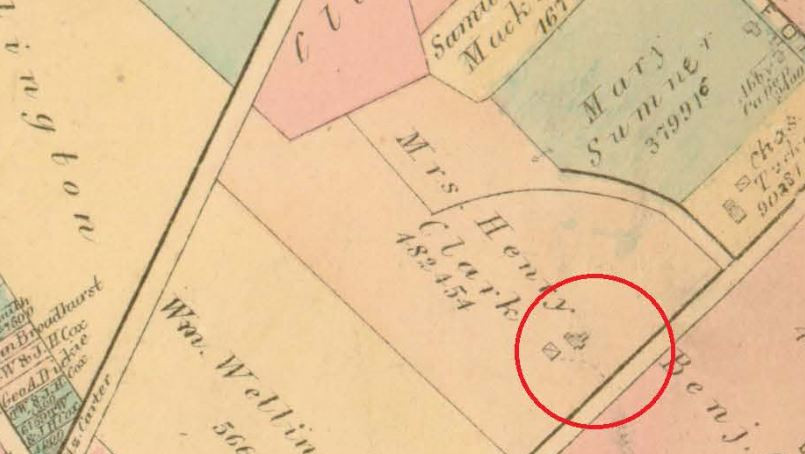

It was not until 1895 that James Henry Clark and his mother Mary J. Clark joined the movement of other Dorchester landowners and divided their 11.25 acres of land into 61 lots, retaining six parcels as their home and selling the rest. However, unlike other Dorchester landowners, the chose to remain in the neighborhood.

While expansions and advancements in transportation clearly impacted the farm, they were slower to reach the outskirts and never quite reached the farm’s immediate neighborhood. Ms. Walsh notes that, “It does not appear that Norfolk Street near the Clark farm hosted a streetcar line, although in 1906 electric streetcar trackage was extended further south along Blue Hill Avenue one block to the west…Development in this part of Mattapan near the Clark farm accelerated as a result, causing the Clark’s lots to be quickly filled with three-deckers within the next ten years.”

Advancements in transportation allowed for rapid suburbanization to accommodate Boston’s fast growing population throughout the city’s neighborhoods. However, at the Fowler Clark Epstein Farm, the Clarks continued to live comfortably on their three-quarter acre farm and preserved that precious space- in an increasingly packed neighborhood before selling it to another long-standing neighbor–The Epstein family.