28 Nov 2017 The Legacy of Publishers Ticknor and Fields at the Old Corner Bookstore, Part 1

Literary historian Rob Velella recently spoke at the Old South Meetinghouse on the extraordinary history of Ticknor and Fields whose 19th century publishing hegemony made the Old Corner Bookstore one of the most importance places in American literary history. Rob graciously permitted HBI to re-print his remarks. This is the first of four installments.

The term “American renaissance” was coined in the 1940s as a reference to a period in United States literature that saw a blossoming of important writings and writers. It was an era where books became associated with a national identity, where certain specific writers began shaping the legends of our relatively new country. Names like Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Henry David Thoreau became iconic and their work came to represent the United States as a whole.

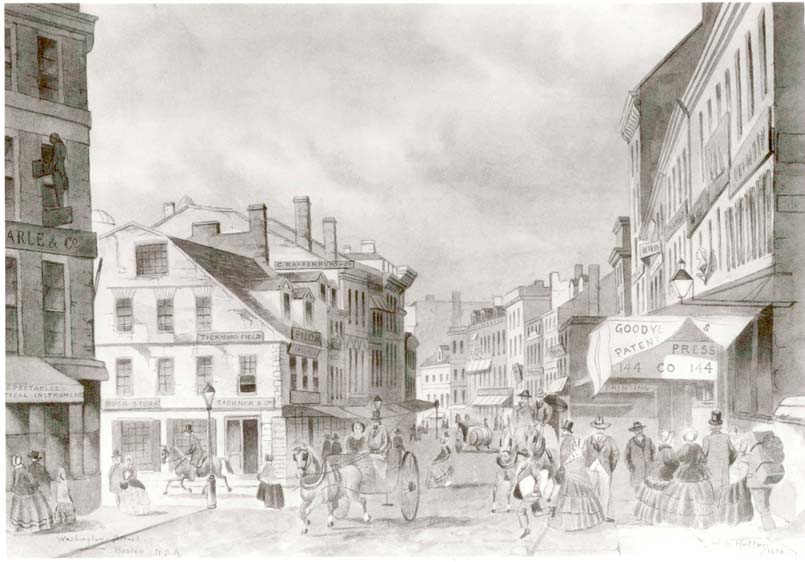

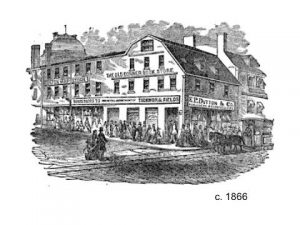

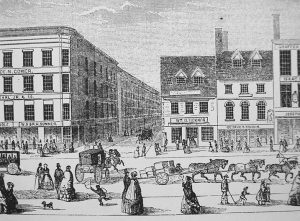

And at the center of it all was an Old Corner Bookstore in Boston.

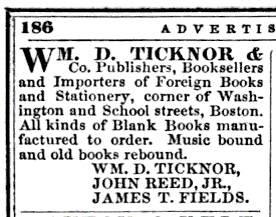

The building which still stands at the corner of Washington and School Streets dates to the year 1711. It did not become a bookstore until 1828 under a company named Carter and Hendee and, five years later, a publisher named William Davis Ticknor began leasing the space. Ticknor was born in a town called Lebanon, New Hampshire, the oldest of nine children. Ticknor was about 22 years old when he partnered with a man named John Allen to form the bookselling house of Allen and Ticknor. He had no previous experience in the book industry. About a year later , Allen left the business and Ticknor ran things on his own under the name William D. Ticknor and Company.

, Allen left the business and Ticknor ran things on his own under the name William D. Ticknor and Company.

In the beginning, Ticknor and Company was mostly a bookstore, but it also was a publisher… sort of. But, picture it as an early version of print-on-demand, or maybe like a Kinko’s: Like most other printers of the time, they did small jobs like stationary, calling cards, and self-published books, usually in small quantities. One of those books, paid for at the personal expense of the author, was An Appeal in Favor of that Class of Americans Called Africans by Lydia Maria Child in 1833. It is believed to be the first significant book to speak out against slavery.

This was good timing. It was the beginning of a boom in the industry, where access to materials, advancements in technology, growing literacy rates, and good postage all combined to mark the importance of printing – particularly in the medium of periodicals. Ticknor and Company printed those as well, but they weren’t really a “publisher” at the time – they were a printer. And, actually, in the beginning their main role was as a retailer selling books – like the name Old Corner Bookstore implies – but many of those books were inconsequential and certainly not great works of literature.

The company almost didn’t survive amidst the economic turmoil of the 1830s. In November 1835, Ticknor had to turn over some of his assets to pay off creditors and he had to cease operations for a few months. Eventually he brought in another investor named John Reed, Jr. In 1837, the year of a famous Bank Panic, he did not publish a single book. That decade, in general, the printers focused not on literature like poetry but on children’s books and religious pamphlets.

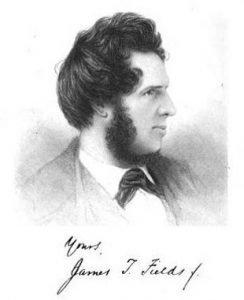

In inheriting the Old Corner Bookstore from the previous owners, William Ticknor also inherited a precocious teenager named James T. Fields. Fields had started working with the first bookstore at the Old Corner when he was 14 – yes, really, when he was 14 years old. Born in New Hampshire like Ticknor, he lost his father at three years old. In 1831, he was in Boston working with the printers Carter and Hendee at the Old Corner. He later frequently said he chose to go into a book-shop for work “because he thought he could sit behind the counter and read all day; but the first thing he was told was that [he was] not allowed to read in business hours.” As it turns out his childhood interest in books made him a really good bookseller. He had a power, his colleagues said, “of seeing a person enter the shop and predicting what book was wanted before the wish was expressed… and he seldom made a  miss.”

miss.”

By 1839, at 22 years old, he was junior partner under William Ticknor. Ticknor was the businessman and Fields was the literary man – the talent scout, the schmoozer. Ticknor knew business, but Fields knew books. And the combination worked. Eventually.

We have to remember that this was very early in United States history and the nation was still in its infancy. Although the thirteen colonies had declared independence in 1776, the fact is that the United States remain dependent on Europe in economy and in culture. This was true for literary culture, too. Although early Americans had a flourishing newspaper industry, and early American writing produced some great political or religious essays and early histories and biographies, American fiction was slow to develop. The argument had been that a nation and its people needed a long tradition of storytelling before fiction could draw from it. Most famously, British critic Sydney Smith in 1820 wrote, “The Americans are a brave, industrious, and acute people, but they have hitherto given no indication of genius… In the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book? or goes to an American play? or looks at an American picture or statue?”

As such, American readers looking for quality fiction turned to European writers. The country was too young and had no stories to tell. Plus, the country was still trying to figure out what it was and how it would survive – politically, economically, practically, not in a cultural sense. As such, the expectation among American readers was that quality literature came from abroad. And Ticknor & Fields took advantage of that market by reprinting the works of European authors.

The book industry was growing rapidly. In 1820, when Smith offered his criticism, the US book industry was worth $2.5 million; it would grow to $12.5 million in the next thirty years. With this, technology was rapidly improving – everything from the way ink was produced, to how paper was rolled, to how illustrations were added, to the machinery that actually did the printing. And literacy was increasing exponentially: By 1860, between 91 and 93% of white Americans were literate. This made up the largest American reading audience in history up to that point.

By the 1840s, the Old Corner Bookstore was publishing more than just British reprints; it also included books by Massachusetts writers John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. By 1843, they were also offering something called “royalties” to its authors – a first in the United States. For his poetry collection Lays of My Home, author John Greenleaf Whittier was offered ten percent off the book’s sales. That number eventually became a standard price.

By 1849, the imprint housed at the Old Corner Bookstore was renamed Ticknor & Fields. Eventually, for a time, they created a standardized cover for their books – a beautiful patterned brown cover with a recognizable font on the spine. More than just uniformity, the design assured readers that the book met the quality standards of Ticknor & Fields and that the text needed no gimmicks to stand out. By the 1850s, they were also publishing fancier collectible editions bound in blue cloth with gold edges – the so-called “blue and gold” editions. Or, sometimes they produced inexpensive pocket editions for those who could not afford the fancy versions. Within the pages, too, books published by Ticknor & Fields often also included listings of their other publications, including upcoming publications, to help advertise and promote their other assets. What made them different as a company, too, was that they were interested in cultivating good literature, not just turning a profit. To do this, Ticknor and especially Fields worked hard to befriend their authors and support them in a more personal way.

We can thank James Fields in particular for being successful on that front. As one friend wrote about him, “Of warm friends and familiar acquaintances probably no man ever living in Boston had a great number. He made friends, facile as a conjurer, with an almost dangerous ease… Wherever he went was geniality. I could not understand how it was possible for one man to carry so many intimacies.”

Fields had an office in the Old Corner that was separated from the shop by a green curtain. There are many accounts of that green curtain that at any time could also be hiding one of the greatest literary lights of the generation – a fact that drew customers to the Corner just as much as the books themselves. Some said, with exaggeration, that “all Boston may be said to pass through [the Old Corner Book Store] in a day.” As one writer recalled:

Fields had an office in the Old Corner that was separated from the shop by a green curtain. There are many accounts of that green curtain that at any time could also be hiding one of the greatest literary lights of the generation – a fact that drew customers to the Corner just as much as the books themselves. Some said, with exaggeration, that “all Boston may be said to pass through [the Old Corner Book Store] in a day.” As one writer recalled:

“The annals of publishing and the traditions of publishers in this country will always mention the little Corner Bookstore in Boston as you turn out of Washington Street into School Street, and those who recall it in other days will always remember the curtained desk at which poet and philosopher and historian and divine, and the doubting, timid young author, were sure to see the bright face and to hear the hearty welcome of James T. Fields. What a crowded, busy shop it was, with the shelves full of books, and piles of books upon the counters and tables, and loiterers tasting them with their eyes, and turning the glossy new pages — loiterers at whom you looked curiously, suspecting them to be makers of books as well as readers. You knew that you might be seeing there in the flesh and in common clothes the famous men and women whose genius and skill made the old world a new world for every one upon whom their spell lay. Suddenly, from behind the green curtain, came a ripple of laughter, then a burst, a chorus; gay voices of two or three or more, but always of one — the one who sat at the desk and whose place was behind the curtain, the literary partner of the house, the friend of the celebrated circle which has made the Boston of the middle of this century… justly renowned.”