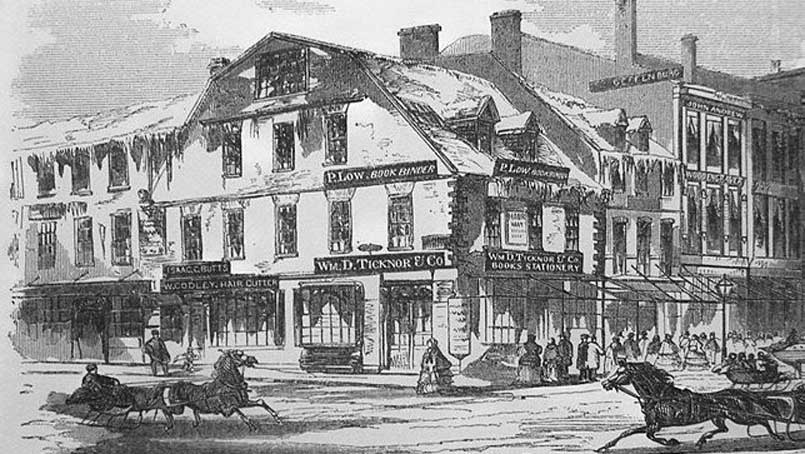

12 Dec The Legacy of Publishers Ticknor and Fields at the Old Corner Bookstore, Part 2

James T. Fields’ Loyal Authors and the Path to Walden

Literary historian Rob Velella recently spoke at the Old South Meetinghouse on the extraordinary history of Ticknor and Fields whose 19th century publishing hegemony made the Old Corner Bookstore one of the most importance places in American literary history. Rob graciously permitted HBI to re-print his remarks. This is the second of four installments.

For his own part, James T. Fields loved being at the center of the growing literary culture of New England. Years later, he reflected on the conversations he would share about his days with authors. As he wrote, “To converse with them and of them… is one of the delights of existence, and I am never tired of answering questions about them, or gossiping of my own free will as to their every-day life and manners.”

This positive outlook was an important aspect of the business of Ticknor & Fields. It was easy for authors to have negative experiences with their publishers or the publishing industry in general. Take, for example, Edgar Allan Poe, whose first book Tamerlane and Other Poems was published in Boston in 1827 – at his own expense. We believe he could only afford 50 self-published copies. Only a few copies remain today and it is considered one of the rarest first editions in American literature. One copy in 2009 sold for $662,500 at auction. But in 1827, only one catalogue even acknowledged its existence.

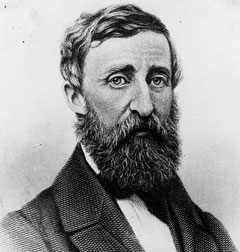

Let’s fast forward to more than 20 years later, and focus on another up-and-coming writer who would become more appreciated after his death: Henry David Thoreau. Thoreau had been shopping around a manuscript based on his personal experiences and observations of nature. The book, based on an excursion with his brother, was called A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Ticknor & Fields originally rejected it, then asked if Thoreau would pay for the printing costs out of pocket: $450 for one thousand copies. Thoreau couldn’t pay, so he turned to a publisher named James Munroe. Munroe offered to pay for the printing of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, but take the cost out of Thoreau’s profits. If the book didn’t sell, he warned, Thoreau would have to reimburse them for the expense. His friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson had published with the same company and done well, so he gave it a shot.

Let’s fast forward to more than 20 years later, and focus on another up-and-coming writer who would become more appreciated after his death: Henry David Thoreau. Thoreau had been shopping around a manuscript based on his personal experiences and observations of nature. The book, based on an excursion with his brother, was called A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers. Ticknor & Fields originally rejected it, then asked if Thoreau would pay for the printing costs out of pocket: $450 for one thousand copies. Thoreau couldn’t pay, so he turned to a publisher named James Munroe. Munroe offered to pay for the printing of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers, but take the cost out of Thoreau’s profits. If the book didn’t sell, he warned, Thoreau would have to reimburse them for the expense. His friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson had published with the same company and done well, so he gave it a shot.

The book was published in May 1849. But, the problem was James Munroe. As one recent biographer of Thoreau noted, Munroe “didn’t publish books; he printed them.” He had no distribution system, did not assist in getting critics to publish reviews, and certainly did not otherwise promote or advertise the book. Like self-published authors today, it was up to Thoreau to get people to buy his book. But Thoreau was not well-known or well-connected, and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers was a personal and professional failure. Less than 20% of the copies were sold and it took Thoreau four years to pay off the cost to print it. Famously, in October 1853, when he bought back all the unsold copies from Munroe, Thoreau bitterly wrote in his journal, “October 28, 1853, “I have now a library of nearly 900 volumes over 700 of which I wrote myself.” “This is authorship,” he added.

The book was published in May 1849. But, the problem was James Munroe. As one recent biographer of Thoreau noted, Munroe “didn’t publish books; he printed them.” He had no distribution system, did not assist in getting critics to publish reviews, and certainly did not otherwise promote or advertise the book. Like self-published authors today, it was up to Thoreau to get people to buy his book. But Thoreau was not well-known or well-connected, and A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers was a personal and professional failure. Less than 20% of the copies were sold and it took Thoreau four years to pay off the cost to print it. Famously, in October 1853, when he bought back all the unsold copies from Munroe, Thoreau bitterly wrote in his journal, “October 28, 1853, “I have now a library of nearly 900 volumes over 700 of which I wrote myself.” “This is authorship,” he added.

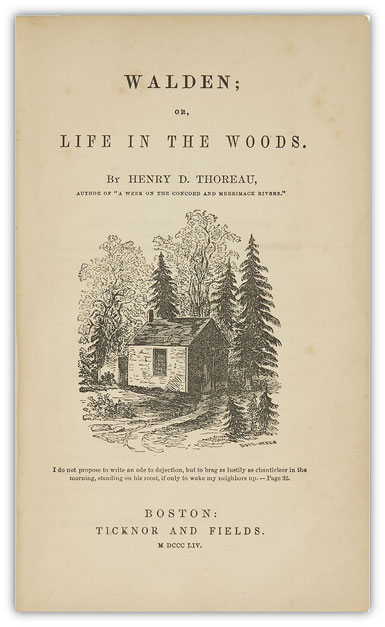

Thoreau had slightly better luck with his book Walden, which was inspired by his time living alone at Walden Pond in Concord. He spent about four times thinking about and writing this book than he did actually living at the pond. It started off in pieces that Thoreau presented as lectures before going through several drafts in book form. 2000 copies of Walden; or, Life in the Woods was finally published in August 1854 – by Ticknor & Fields. It took years to sell out that first edition, but the book was apparently quite positively received. Emerson wrote that, “All American kind are delighted with ‘Walden’ as far as they have dared to say.” In 1861, an admirer from New Hampshire wrote asking for a copy of Walden. Thoreau responded that he did not have any, but he had plenty of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers and he could have one of those – for one dollar and twenty-five cents.

Thoreau had slightly better luck with his book Walden, which was inspired by his time living alone at Walden Pond in Concord. He spent about four times thinking about and writing this book than he did actually living at the pond. It started off in pieces that Thoreau presented as lectures before going through several drafts in book form. 2000 copies of Walden; or, Life in the Woods was finally published in August 1854 – by Ticknor & Fields. It took years to sell out that first edition, but the book was apparently quite positively received. Emerson wrote that, “All American kind are delighted with ‘Walden’ as far as they have dared to say.” In 1861, an admirer from New Hampshire wrote asking for a copy of Walden. Thoreau responded that he did not have any, but he had plenty of A Week on the Concord and Merrimack Rivers and he could have one of those – for one dollar and twenty-five cents.

“He always smells of the pine woods.” That’s what James T. Fields once said of Thoreau. As Thoreau neared his death, Fields asked him to revise some of his essays for publication in the Atlantic Monthly. Thoreau agreed, under condition that “no sentiment or sentence be altered or omitted without my consent” – a request based on frustrations from previous editors and publishers. Ticknor also visited Thoreau in his final days and asked to acquire the rights to all his previous works in the hopes of publishing a fancy uniform edition.

Fields is partly responsible for kickstarting the so-called “American Renaissance” in literature. It should be mentioned that the era identified as the Renaissance is somewhat cherry-picked because it focuses on very male and very white authorship and centers much of the literature on New England. The term was first coined in 1941 by a scholar who believed the authors he chose best represented the literature of democracy. The call to break away from British traditions dated pretty early, from people like Emerson who called for a distinctly American literature in his “American Scholar” speech in 1837. And scholars credit Emerson directly for starting the movement with his 1850 book Representative Men. Ticknor & Fields played their part by publishing not only Walden in 1854, but also The Scarlet Letter in 1850.