27 Feb 2018 The Legacy of Publishers Ticknor and Fields at the Old Corner Bookstore

Literary historian Rob Velella presents the fourth of four installment of a presentation made in the fall of 2017 at the Old South Meetinghouse on the extraordinary history of Ticknor and Fields whose 19th century publishing hegemony made the Old Corner Bookstore one of the most importance places in American literary history.

Ticknor & Fields Leaves the Old Corner Bookstore

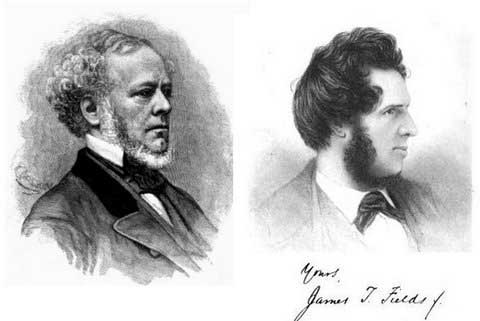

James T. Fields did whatever it took to urge his writers to work hard– sometimes going too far. With Nathaniel Hawthorne, in 1863 and 1864, he paid him in advance, suggested a title, and published an announcement of his forthcoming work – all without Hawthorne agreeing. Hawthorne never finished that particular work, and Fields ended up placing the incomplete manuscript on Hawthorne’s casket during his funeral, where Fields actually served as a pallbearer. Not long after, Hawthorne’s widow Sophia Peabody threatened to sue Fields because the company had promised “to pay the highest rate of copyright it ever paid” in royalties, and she felt he stiffed her. The story is just to emphasize that Fields always did what he thought was best to push his authors. And he often did whatever it took to keep them happy. For Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, for example, he threw parties in his honor and bought him concert tickets. And, of course, he kissed up: “It strikes me the author of ‘Evangeline’ does better and better every time he strikes the lyre,” he once told Longfellow. When negative reviews were published, he would write to his authors and reassure them the critic was wrong – and he might even threaten to boycott that critic. His loyalty – and his generous royalties – certainly did well for the company.

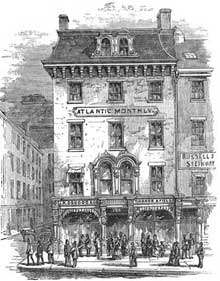

But these practices also added to costs, and the company’s superstar authors required more and more money to maintain. The overhead of the business also began to grow, between rent, the purchases of new equipment and supplies, and a growing staff. They also began purchasing copyrights and investing in periodicals – including purchasing the Atlantic Monthly in 1859. With the Atlantic Monthly, they became the first publishers of now-famous works like Longfellow’s poem “Paul Revere’s Ride,” Julia Ward Howe’s “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and Edward Everett Hale’s story “The Man Without a Country,” as well as various works by Charles W. Chesnutt, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Bret Harte, and Mark Twain.

But these practices also added to costs, and the company’s superstar authors required more and more money to maintain. The overhead of the business also began to grow, between rent, the purchases of new equipment and supplies, and a growing staff. They also began purchasing copyrights and investing in periodicals – including purchasing the Atlantic Monthly in 1859. With the Atlantic Monthly, they became the first publishers of now-famous works like Longfellow’s poem “Paul Revere’s Ride,” Julia Ward Howe’s “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” and Edward Everett Hale’s story “The Man Without a Country,” as well as various works by Charles W. Chesnutt, Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Bret Harte, and Mark Twain.

Ticknor had been the main businessman of Ticknor & Fields and, after his death, things began to change. They sold their retail establishment at the end of 1864 and ended their lease at the Old Corner Bookstore. They moved to Tremont Street and were eventually reorganized as Fields, Osgood & Co. after Ticknor’s son Howard Ticknor withdrew from the company and a man named James R. Osgood came in as a partner.

Fields may have seen that he was now piloting a sinking ship and retired from the firm immediately after New Year’s in January 1871. He was 53 years old and, he claimed, he wanted to focus on his own writing. The company became James R. Osgood & Co., but was soon in serious financial difficulty. Osgood sold off assets and moved to Franklin Street to keep the company afloat. The Great Boston Fire of November 1872 devastated the city’s publishing industry and that year Osgood & Co. wrote of a financial loss of $48,366.83 – which I would today calculate at about $1 million.

And I think the loss of both Ticknor and Fields also led even the most loyal of the company’s authors to wonder if it was time to move on. The best example, I think, is Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Ticknor & Fields had made Longfellow the highest-paid poet in American history, enough that he was able to retire from his full-time day job as a professor at Harvard, and focus solely on his writing. After 25 or 30 years with the same publisher, by 1874, he was shopping around for a new publisher. To appease his most popular poet, Osgood nervously offered him a deal: a retainer or annuity equivalent to $92,000 a year today, even if Longfellow never published a thing. Although I think this is both a great deal for Longfellow and an amazing historical point in American publishing, it also smells of desperation on the part of Osgood, who never quite lived up to his predecessors.

Eventually the company merged with Hurd & Houghton to form Houghton, Osgood & Co. – which, in turn, eventually evolved into Houghton Mifflin, now Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

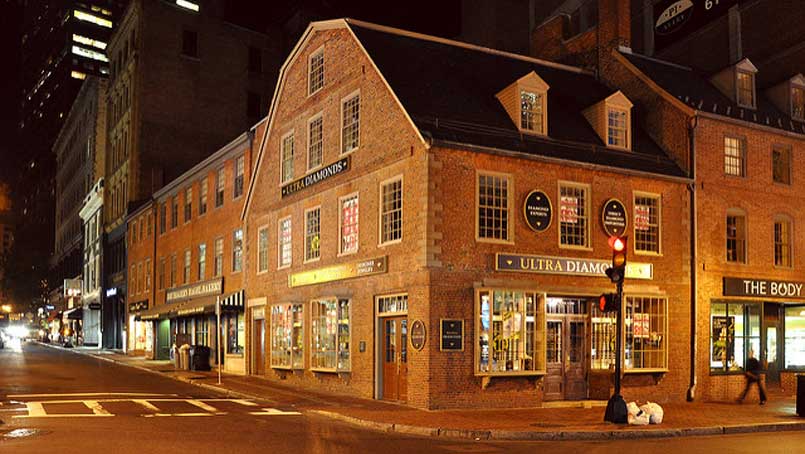

The Old Corner Bookstore itself continued selling books until about 1903. After that, the building shifted various retail roles for several decades. In 1960, a group of Bostonians fought to preserve the Old Corner from development. A nonprofit company raised $275,000 to buy the building and restore it and the Boston Globe assumed a long-term lease until the 1990s. More recently, it has hosted other ventures like a diamond store and now a certain chain restaurant that will not be named. But, regardless of its use, I for one am thankful that the building exists as a reminder of this era that created the American publishing industry as we know it. And that it sits on the Freedom Trail is also a good reminder of the role that literature played in expanding freedom.

Looking back at this complicated history of a complicated publishing house, ultimately, what is the legacy of Ticknor & Fields? And its headquarters, the Old Corner Bookstore? In the 19th century writer George William Curtis referred to the Bookstore as “the hub of the hub.” Others called it the “American Parnassus,” referencing the Greek mountain that, according to mythology, was home of the muses.

I think there are a few things that make the story of Ticknor & Fields unique. For one, they built up a circle of loyal authors – not just clients for whom they printed works, but partners in a shifting publishing industry where author and publisher both played vital roles in a book’s success. They believed in literature more than in profit, and believed that the best authors deserved to be financially compensated for their efforts. They also centered New England as the seat of literary and intellectual culture, and their influence is seen in the canon even today. They pushed for a certain time of genteel, morally uplifting type of writing, too, that impacted the industry as a whole and other authors throughout the country – such that authors that did not write to offer positive life instruction were inevitably unsuccessful.

Or, as on article in 1880 summed it up:

“The names of Ticknor & Fields are imperishably connected with one of the most brilliant chapters of American literary history, and ‘the Old Corner Bookstore,’ while those names rested overs its doors, must be regarded as the birthplace, commercially speaking, if not intellectually, of more of the books that have established the American literary name than can be credit to any other spot.”*

*The Literary World, September 25, 1880: p. 324

The Legacy of Publishers Ticknor and Fields at the Old Corner Bookstore